Your cart is currently empty!

Is your child’s target weight a gift to the eating disorder? One-Size-Fits-All versus Growth Charts

Your child's target weight might be very wrong

Keeping your child underweight is a gift to the eating disorder. So it's understandable that parents and clinicians want to predict a healthy goal weight. Yet all prediction methods are flawed. The only almost certain thing is that as a minimum, lost weight must be recovered. Your child's real healthy weight will reveal itself when they're well physically and mentally. Meanwhile, the expert care must continue. Too often a person is discharged from treatment just because they've reached a goal weight. Yet your child may need more weight, and they almost certainly need more work on normalising behaviours, and on navigating their life.

A target weight is like a weather forecast

The weather forecast may be for sunshine, but do I take that as certain? No, it's just a prediction. Some sites seem to get it right more often than others. Likewise, all goal weights are estimates, and some calculation methods are overly simplistic.

If the forecast was for sun but it's actually pouring, I take shelter. I don't insist that the sun really is shining. Likewise we must keep assessing our child's needs, rather than get over-focused on a number.

You can skip this page if, very wisely, your clinicians tell you not to focus on a goal weight, and keep doing the work.

* For my main page on weight restoration, and a guide to navigating the uncertainties around weight targets, see 'Weight-restoration: why and how much weight gain?' *

On this page

I'm going to show you two very different approaches used by various clinicians when they give patients a weight target.

- One is 'middle-size-fits-all' — you wouldn't choose shoes that way, and neither should anyone do this with your child's biological needs. Nor do you insist on sunbathing in the rain, on the basis that the average of weather records shows it 'should' be sunny. Do not rely on numbers like '100 percent weight for height' or 'median BMI'. By definition they fail half of our kids.

- The other method is better because it predicts healthy weight from a plot of your own child's growth history. So there's more personalisation. But you still can't rely on that number because an individual's growth isn't so neat and tidy.

- I'll show you how the 2 methods can give vastly different predictions.

- And I'll urge you to embrace uncertainty: you'll only know your child is truly weight recovered when all the physical and mental signs are good, not when you reach a number predicted by either method.

A weight target that could be so wrong that your child will stay stuck

If you're in a hurry, jump to the infographic below. If you do read this page, you'll be able to tell which method has been used for your son or daughter, and you'll be able to have an informed discussion about your child's needs with clinicians.

If you're a clinician and you're using a calculator or app to work out target weight, I hope that what follows will prompt you to follow the lead of some of our top experts and throw away the calculator. If you're using growth charts, I hope that this page and my other page on growth charts will help you appreciate how any predictions are approximate.

I'll explain how the middle-size-fits-all method is likely to fail around half of patients. That's because you can't beat an eating disorder if you're attached to a weight target that has been set too low. People who are still suffering physically and/or mentally are failed when treatment stops just because they've reached a particular number.

These messages from parents should ring alarm bells:

- 'She's at 95 percent, so we're nearly there' (if I ask, 95 percent of what, they don't know, because they thought they'd be judged if they asked.)

- 'His BMI is 20, so he's being discharged next week' ('the eating disorder is as strong as ever, but the young man has been told that if he doesn't take responsibility for his recovery the service can't help him')

- 'She has a massive exercise compulsion and she's been told when she's reached 90 percent she can return to her swimming team.'

- 'The doctor says his labs and heart rate are concerning, but the therapist says as he's at xx percent weight-for-height he's OK to go to school'

- 'My 12-year old lost 20 pounds, which according to the doctor means she's now healthy' (the weight loss puts this girl in danger, and it's irrelevant that her BMI is now 'normal')

But first, why a weight target?

Why indeed? Some experts make the case that a goal weight is useful, and some say not. My main post on weight restoration (here), tells you what you need to know about weight in recovery from an eating disorder, and discusses pros and cons of having a weight target.

Growth Chart + Adjustments, versus One-Size-Fits-All

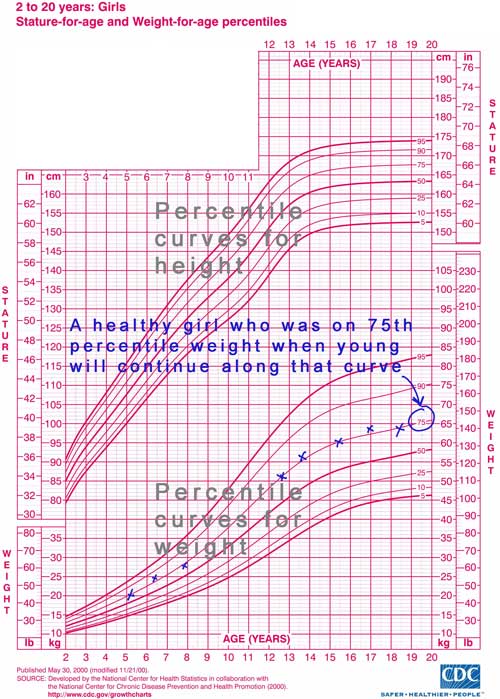

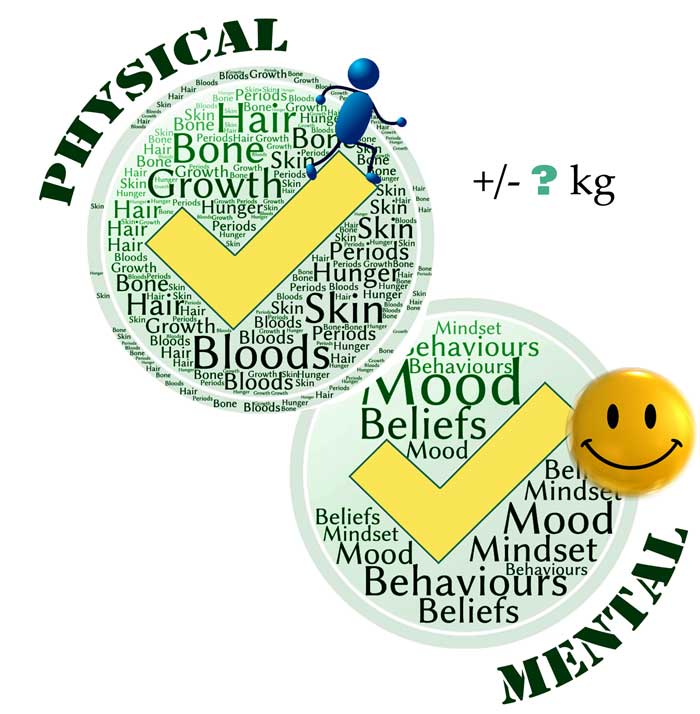

I'll show you the differences between the two approaches. I produced this infographic (which you're welcome to copy and share, as long as you keep it just as it is – and please click on it to get a better quality image) to give you a quick idea of what it's all about. With the example I picked, the person's target weight would differ by 10 kg (22 pounds).

The top experts use an individualised approach

By an individualised approach, I mean that the expert will regularly assess your child's changing physical and mental state. While they may plot your child's growth on a percentile chart, they won't pick a goal weight or range from it — it will just be part of a wider picture. And they will certainly not take a goal number from a medium BMI calculator).

In the infographic above, they will be in the left hand column. And they will tell you that any goal weight is full of uncertainty, and will have to be reviewed and adjusted. Also, there are great clinicians who do not give a goal weight.

On the other hand, any clinicians who are on the right hand side of my infographic, setting goal weight based on 100% weight for height or 100% of median BMI or 50th centile BMI, are out of step with current recommendations.

Here are just a few quotes from experts.

For many more, please head over to my page 'Experts say, "Recovery weight should be individualized" Yet middle-size-fits-all targets are still common'

'Treatment goal weight should take into account premorbid trajectories for height, weight and body mass index; age at pubertal onset; and current pubertal stage"

Position Paper of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine (USA) (2016)

"There is no one right size that fits all when it comes to healthy weight after anorexia nervosa. Thus anyone who uses an equation (such as a BMI or ideal body weight calculator) or simplifies this complicated situation is relying on tools that are inadequate."

Dr Jennifer Gaudiani, internist and expert on the medical complications of eating disorders, in 'Weight goals in anorexia nervosa treatment'

"The idea that […] everyone should be at medium BMI – that is just not the case and not appropriate"

Daniel Le Grange, co-author of the FBT treatment manual, in this webinar

"In young individuals, a “biologically appropriate weight” is associated with normal historical development."

AED Guidebook for Nutrition Treatment of Eating Disorders (2020)

"Goal weights typically take into account patient’s height, age, premorbid growth curve percentiles for height and weight, prior growth trajectory, growth potential, pubertal stage, anthropometric measurements and other physiological factors"

Faust et al (2013) 'Resumption of menses in anorexia nervosa during a course of family-based treatment'

A one-size-fits-all model is still tragically common

If your child's weight target is a particular BMI or 'weight-for-height', then the clinicians are almost certainly using a method sometimes called the 'BMI method'. As I'll show, it's a one-size-fits-all model. Or more precisely, a middle-size-fits-all.

The BMI method uses big BMI surveys from the population (well, often it's a white american population). The assumption is that your child will be fine in the middle: the median.

Imagine I'm about to open a shoe shop and I'm busy ordering stock. I'm looking at statistical charts and I'm thinking, frankly, why so many sizes? Too much uncertainty! I'll sell one stylish model in one size for each age, and everyone will be happy!

Some clinicians — usually not specialised in eating disorders — believe that weight doesn't need to be individualised, and they would dismiss the shoe-size / weight analogy. For them, mid-range is usually all anyone needs. Some even set the goal weight lower for fear of scaring the patient — a 'small-size-fits-all' model which can lock even more patients into their eating disorder, as I discuss on my main weight-restoration page.

If I'd been selling shoes to the unfortunate elite women in ancient China, I'd only have stocked tiny, bone-crunching shoes.

The calculator is way off

I used to think that 'weight-for-height' apps, calculators and Excel spreadsheets — all using a middle-size-fits-all (median BMI) ideal weight — would at least give a rough estimate. But you need only take a peak at a BMI chart (girls, boys) to appreciate the wide range of BMIs in a normal population. A median BMI will only fit the most 'average' patients. For everyone else the calculator is so very wrong that it doesn't even cough up a decent ballpark figure.

And as I'm going to show you, the calculator churns out a very different number from what you might get from a growth chart.

How a growth chart is used (imperfectly) as part of the healthy weight prediction

First off, I want to be clear that growth charts cannot predict your child's healthy weight. All you're doing is making a guess, based on the weight of kids at various ages. I explain here how this doesn't not take into account the variability of each child — for instance, when a growth spurt might be due. So any prediction made with a growth chart needs to be modified as your child's mental and physical state evolves.

In addition, no expert will use only a growth chart to estimate healthy weight.

With this caveat, I'll show you how a growth chart is used. (You may prefer to see a demo on my YouTube and then you can skip to the next section of this page.

Below is an example of a growth chart for girls, with curves indicating percentiles.

* I explain percentiles here *

Here's the principle: if a girl was on the 75th percentile curve for weight when young and healthy, we predict that this is where she'll need to be throughout life to continue being healthy. I want to stress this is a very imperfect guide: in real life, healthy youngsters are deviating temporarily or permanently from percentile curves.

Dig out all the weight data you have from your child’s early years. Stature (height) data are useful too: they may show that growth was stunted by malnourishment. They may give clues on growth spurts that are due or that have already happened.

Your child could have started restricting quite a bit earlier than you think, or they may have lost weight during various illnesses or just because of metabolic factors that form part of the eating disorder risk. So go back as many years as you can. Indeed, people who have anorexia in their teens have often dropped off their growth curve as toddlers.

On the example below I’ve plotted the weight of Jo, a girl who tracked on the 75th percentile for weight until age 12. The next time she was weighed, on her 14th birthday, she weighed 50kg (110lbs). Can you see how, while she gained 2 kilos, she dropped from the 75th to the 50th percentile curve?

I'm not showing her height data, but perhaps her height has also dropped off its percentile curve, indicating some growth stunting. Her body will need fuel to catch up.

(Note: We could also plot her growth on a BMI chart, by the way. I mention it because some therapists do that. Again, the assumption is she should track on a particular percentile curve — the 60th percentile for example. So a therapist might say the target BMI is 60th percentile, and work out the target weight from that. But BMI is a bit volatile (rather wiggly on a chart), so you'll get a clearer picture sticking to a height chart and a weight chart.)

So we get to work on refeeding, which takes time. Let's look at where she might need to be in, say, six months' time. No point in giving her a target that will be obsolete by the time she gets there.

From the chart, we look at the 75th percentile curve and find a target weight of 58 kg (128lbs).

Health is not a number

In practice, when we plot growth charts we discover that over the years, our children have oscillated around a range of percentiles. Also, the 'rule' that a child's healthy height or weight stays on one curve is alluring, but those curves are statistical compilations. Healthy children will have growth spurts where, for a while, they deviate from those curves. Also, we've all seen kids who used to be average height and suddenly became giants.

And what if your child fell off their growth percentile really early on, and that was not serving their health needs. What if their anxious nature stopped them from eating to their needs, for example?

And then, a growth chart only provides one of the indicators that experts use to estimate healthy weight.

In short, take all predictions with a pinch of uncertainty.

So any target weight is, more sensibly, a target range… and even that needs to be reviewed as you observe your child's physical and mental state.

Be careful: if you give your child a range, they will probably hear the upper number as a maximum and may well restrict when they get close to it. So it can be better to state a minimum. Even better, for many youngsters: don't give any numbers.

Adjusting for physical and mental state

A growth chart only gives part of the story. The weight at which your child turns out to be healthy — physically and mentally — may differ. In my main page on weight restoration I say more about that. Remember, also, that the chart is only showing a snapshot of data for a particular population — probably mostly white-Caucasian, and doesn't show the speed of growth (e.g. growth spurts) of individuals.

How is a 'middle-size-fits-all' weight target calculated?

Let's move on to the middle-size-fits-all. In scientific papers it may be called the BMI (or median BMI) method, or it may refer to the use of 'normative population data'.

This approach doesn't look at your child's personal situation but at population surveys. And every so lazily, it just plucks out the average and serves it to you as a recommendation.

Clinicians share with each other apps or Excel spreadsheets to make this simple. So simple that the prediction has an aura of certainty. I know of clinicians who have no idea what's behind the 'percent weight-for-height' number that they report so diligently in the patient notes. So I'll explain now.

Let's return to our 14-year old girl. Her growth chart hinted that she urgently needs to increase her weight from 50 to 58 kg. How does that compare to the BMI app's results?

You type in her sex, age and height. The answer pops up: her 'ideal' or 'target' weight is 51 kg.

More terminology for you: that's the weight that corresponds to the median BMI, or the 50th percentile BMI, or to 100 percent weight-for-height. ('Median' is a kind of average: it's the middle point in a range. I explain BMI and weight-for-height (WFH) here. ).

Giving this girl a 51 kg target is like having her walk into a shoe shop and insisting that a middle-sized shoe will fit her.

Let's be clear: any girl of that age and height will get that exact same target weight. Yet out there in the real world, girls of that age and height come in a wide range of weights:

The only bit of personalisation that goes into a weight-for-height figure is sex, age and height. Not family body-types, genetics, metabolism, puberty, growth spurt needs, healing needs — nothing.

For a clinician relying on a calculator, this girl, who weighs 50kg, is so close to the app's target weight of 51kg that she really doesn't need to gain weight. Sadly it's common for therapists to say that 95 percent weight-for-height is plenty — they hate to stress out a patient by aiming for more. This girl is already at a 'generous' 98 percent (in case you're wondering, the app coughs up the 98, but you can also work it out by dividing 50 by 51).

The clinician hasn't asked for the girl's height or weight history, so all they see is a girl with an eating disorder who doesn't need weight gain 'because' her BMI is perfectly average. They don't see any need for weight gain, and most worryingly, they might not see any need to check her health. Yet this girl's health is very much at risk right now, given how much she's dropped off her weight curve. (To read more on this from an expert paediatrician, see The misuse of BMI in diagnosis of pediatric eating disorders by Julie O'Toole)

Truly, this happens a lot, especially with GPs. As I was writing this piece I got this naive email from a parent: 'My daughter (13 years) has lost at least 10 kilos in the last 3 months [that's 22 pounds], but she is still at the 25th centile, so no need to admit her or do bloods.' Luckily, the GP who gave this flawed advice did refer her to the eating disorder service. They recognised the weight suppression and gave energetic and competent care.

In summary: According to her growth chart the girl in our example needs to gain 8 kg (20 pounds, or more than 1 stone) as the aim is 58 kg in six month's time. She is currently very underweight and needs to be carefully monitored. A clinician relying on a calculator would say she is fine and doesn't need any weight gain as she is already at 98 percent weight-for-height.

It's even more wrong with height-stunting

With a restricting eating disorder like anorexia, it's common for our children's growth to be halted or slowed down. So, what if in the past year, this girl hadn't grown? Let's plug into the app her current 50 kg, but this time let's say her height is only 158cm.

Now her ‘ideal’ weight comes up not at 51 kg but 48kg. Remember that right now she weighs 50kg. Her eating disorder now has confirmation that she's fat. It tells her she must lose more weight.

The app doesn't know that her growth was stunted. It doesn't know that she's been restricting, that she's lost out on weight, and her body is in 'famine' mode. It's just looking up the middle BMI for girls that height.

This girl's body is crying out for nutrition and energy for growth, yet the 'middle-size-fits-all approach would set her healthy weight 10 kg (22 pounds, or 1.5 stone) lower than indicated by her personal growth chart.

Can you see how a calculator doesn't even give a useful ballpark figure? And I didn't even choose an extreme example. With another child, with different height and weight parameters and a different history, the difference could be even bigger.

Half of our children are kept underweight by the 'middle-size' approach

Because the median BMI, or 100 percent weight-for-height, is in the middle, it's going to be wrong for roughly half of our kids. That's because by definition, half the kids that sex and age have a lower BMI, and half have a higher BMI. That's what a 'median'is.

I'm not worried about the kids whose true healthy weight is below the calculator's target. The 'extra' weight will be used for growth. It won't do any harm. As I explain in my main weight-restoration page there are some good arguments for aiming high.

For the kids whose historical BMI has tracked close to the 50th percentile, both methods for estimating target weight will give roughly the same (imperfect) result. Be ready to adjust and review.

The kids who are in danger are those who need to track at a higher BMI. With the middle-size-fits-all method, the weight target is a gift to their eating disorder.

When a therapist puts their faith in a calculator, the tail is wagging the dog. This teen doesn't yet have her periods at 100 percent weight-for-height? They'll return later. This girl is still skipping school lunch? It's time she took responsibility. This boy is still compulsively exercising? Well, you know, some people never recover.

The question for those who use a calculator is, how can a middle number suit the wide range of human beings that come into their office? It is an extraordinary claim. It needs evidence, not opinion. In science, a theory is invalidated when there is evidence to the contrary. And we have plenty of that. I quote studies further down, and additionally we have numerous first-hand accounts of children who remained very ill at median BMI (and got well when they were eventually supported to gain more weight).

Let's be clear. For roughly half of patients, the calculator will come up with an adequate or generous weight target, statistically speaking. That's on average fifty percent of patients with a chance of a successful treatment outcome. That's statistics, and it's a gamble when it comes to an individual patient. Without considering their growth history, you can't know if they're in the half who will be failed by the calculator.

'My kid is back'

Here's one story from a huge pool of similar stories that are everywhere on parent forums. These stories start with a child who stayed ill for months or years while supposedly 'weight-recovered' using a 'middle-size-fits-all' figure. At long last the child recovers when a new therapist, or the parents insist on a higher weight. There are plenty of similar stories with recovered adults too.

This is the story of a 14-year old boy who was 'stuck' with anorexia at an unsuitable weight:

My son was told that he was fully grown, and that as his BMI was 19, he was now weight-recovered and could maintain his current weight. But he was still terribly ill. He couldn't even drink a glass of orange without major anxiety. Eventually we sacked the therapist and resumed high calorie feeding. It was twice as hard as he had been told a BMI of 19 was PERFECT for him.

With weight gain, he grew another 5 inches. We got him to a BMI of 24 and kept him there. It's made all the difference. My kid is back. For the last two years he's been doing just great, fully functional, and in good recovery.

Where did this BMI of 19 come from? Looking at boys' BMI charts, I see that for a 14-year old it's the median percentile. This boy went from a disastrous 'middle-size-fits-all' to a weight that truly suited him.

What do the top experts say?

As you'll have gathered from the experts I have already quoted on this page, top professionals assess each individual for their needs.

Here are a few papers that explain the problem with a one-size-fits-all approach (it might be referred to as 'the BMI approach') and that strongly recommend that targets are individualised:

"Such methods [using median BMI] are unlikely to gauge the extent of weight recovery needed for individuals whose baseline weight was higher or lower than average, which may not only lead to partial recovery for these individuals."

Lebow et al (2017) 'Is there clinical consensus in defining weight restoration for adolescents with anorexia nervosa?'

"Treatment goal weight for a particular patient cannot simply be read off the charts on the basis of normative population data. Put another way, treatment goal weight is not necessarily the same as the weight associated with median BMI."

Golden et al (2015) "Update on the Medical Management of Eating Disorders in Adolescents"

"Professionals also use growth curves to establish target weights for recovery. Research shows that these curves, when available, are more accurate than using population averages to determine an individual's treatment goal weight."

Lauren Muhlheim in 'When your teen has an eating disorder'

One study Lauren Muhlheim cites is this:

"In most cases, [a growth curve] allows a clinician to easily estimate a patient’s healthy body weight and provides a number that is specific to the individual patient based upon their previous growth parameters, rather than on the population average for age (i.e. the 50th percentile).

Harrison et al 2013 'Growth curves in short supply'

Why does anyone use a middle-size-fits-all target weight?

There are plenty of lovely, caring therapists who use calculators to work out your child's target weight. And BMI charts are everywhere in the health service — I'm guessing they are so ordinary that people might not pause to wonder quite how inaccurate they are for individual use.

Clinicians might be hoping to get a ballpark figure because your child doesn't have any historical data to plot onto a growth chart. Hopefully I've done a good job of highlighting how this figure could be wildly wrong.

On the other hand, I talk to parents who were never asked for their child's growth history. The clinic is relying entirely on a 100% weight-for-height figure. They discharge from treatment at that figure. I hope this post contributes to change.

There is also a tricky shift from research to clinical practice. Researchers need to define 'recovery' as systematically as possible in order to assess treatments. An analogy: if you were comparing various remedies for sleep deprivation, you could set 7 hours of sleep as your benchmark for success (even though some people actually need more, and some less).

For anorexia studies, most researchers have used median BMI as their benchmark. For instance in Lock and Le Grange's landmark study of FBT, for treatment to count as successful, teens had to do well on a behaviours and beliefs questionnaire and they had to reach 95 percent weight-for-height. Let's be clear: that 95 percent is a choice made for the sake of consistency in a moderately big trial. The authors are the first to say that in clinical work, healthy weight is individual.

"Clinically we use individualized weight calculations; this is not possible in research studies as the same outcome needs to be assessed in all participants."

James Lock, co-author of the FBT treatment manual, personal communication, March 2020

Is there any reputable therapist who endorses the 'middle-size-fits-all' approach?

In the world of children and adolescents, I have come across only one reputable researcher and clinician who has put pen to paper to advocate a 'one-size-fits-all' approach. This is Christopher Fairburn, who has researched and written on CBT for eating disorders. His manual advocates a fixed low BMI figure for all adults, a fixed low BMI for older adolescents. Only for younger adolescents does he take age and sex into account by using a 100 percent weight-for-height target. He writes that in his experience, these targets work for most patients. However the success of CBT is not very high (though it is one of the better approaches available to adults — and adults have traditionally been given low weight targets). How much higher would recovery rates be if targets were not only higher, but individualised?

In summary: 95% of what?

I hope this article will help you enquire what a therapist means when they say your child is x-percent weight-recovered. Most likely it's relative to a middle-size-fits-all number from a calculator.

Or when your child is promised that they may resume an activity when they reach a certain weight: where does that number come from? How can anyone predict that your child will be physically and mentally in a good place for this activity?

Final thoughts

There is no number on the scales that can say a child is healthy. Let's keep up the teamwork between parents and clinicians to keep reviewing our children's needs. There is going to be uncertainty about your child's healthy weight, and you'll only know you're there when you're there. Meanwhile let's remember: 'First do no harm', and not throw around incorrect numbers that our children will fixate on.

More help from me:

* Weight-restoration: why and how much weight gain? *

My main page on healthy weight for eating disorder recovery. Why weight gain, how much, danger of a low target weight, buffers, overshoot, ‘stuck’ patients.

* Experts say, "Recovery weight must be individualized" *

A collection of quotes from professional institutions, researchers, clinicians and those who train clinicians

* What do BMI and Weight-For-Height mean? *

What BMI and Weight-for-height (WFH) and BMI z-scores mean, and how they cannot be used for advice. Read this if your child’s therapist uses BMI or WFH.

* My YouTube: 'What is a BMI or '% Weight-for-Height' target, and how wrong it could be' *

* Weight gain in growth spurts *

To help you let go of weight targets, I remind you that youngsters' growth is unpredictable and can go in spurts.

* Weight centile growth charts: why they can’t predict your child’s recovery weight *

How growth charts cannot predict a healthy weight for your child: I show you how they fail to show normal variations in healthy individuals and remind you that you won't know your child is weight-recovered until they get there.

* My YouTube: 'Growth charts and goal weights made simple *

If your child has failed to gain weight with age, or has lost weight, that's weight suppression. Make sure your clinicians aren't only looking at your child's current weight: here's evidence that the amount and speed of weight loss matter at least as much.

* Atypical anorexia diagnosis? Handle with care! *

What's 'atypical anorexia', the issue with weight being declare 'normal' or high, the risk from malnourishment and the need to regain lost weight.

* More on weight and feeding in Chapter 6 of my book and in my Bitesize audio collection *

From others:

* More on target weight on the excellent, parent-led FEAST site: 'Setting target weights in eating disorder treatment'

* Poodle Science: a YouTube from Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH): A short fun video that makes the point that one size does not fit all *

* CDC (american) growth charts for boys and for girls. And here are UK ones. There's also access to WHO (World Health Organization) and CDC charts on mygrowthcharts.com *

Thank you to James Lock, Daniel Le Grange, Ivan Eisler, Esther Blessitt, Rebecka Peebles, and a whole lot of well-informed parents, for helping me write this post.

Last updated on:

Comments

-

Hi. The link to another post regarding extra weight (see below) leads to nowhere… I really need some facts to arm myself with as my daughter is very focused and aware that she is likely to be amongst the lower weight population, and doesn't see why she should gain extra weight just because I say so.

Can anyone help?

The broken link is below the mowest picture of a pink growth chart.

"I'm not worried about the kids whose true healthy weight is below the calculator's target. The 'extra' weight will be used for growth. It won't do any harm. As I explain in THIS post there are some good arguments for aiming high."

-

Hi Beca, I'm glad you flagged up that bad link. I've now fixed it. It goes to a page where I talk about weight restoration and there's a heading "Aim for higher". I hope this helps.

Love, Eva

-

-

Thanks for getting back, Eva, for your thoughtful response and for your link which I have now read.

I get what you say about the overshoot and it makes sense, but I wonder if there's another danger here that needs to be further explored.

Let's take an example of a girl who has been on the 10th percentile all her life and for whom a corresponding "normal" weight might be 43 kgs. In a hospital setting, going by median charts, she would be set a target weight of 52 kgs and they'd try to keep her between 95% and 105% of 52 kgs. So she could be taken to 54.6 kgs.

54.6 kgs is more than 125% of 43 kgs. Doesn't that start getting into territory of increased risk of type 2 diabetes and other morbidities typically associated with being overweight?

When it comes to healthy BMI, it's well known that people of African origin deviate from Caucasian populations in one direction and people of south Asian origin deviate in the other direction. However, I've looked at several texts and there does not seem to be any reference to any comprehensive study on this subject in relation to children.

The most they do, as the MARSiPAN guidance in the UK does, is point to a study by Cole et al (2007). But that is research involving only Singaporean / Korean subjects with no black, Indian or other ethnic groups involved.

I've done some of my own (less than scientifically accurate) research with children of Indian and Pakistani origin. 80% of the children / teenagers I was able to sample fell below the 25th percentile on the (age and sex appropriate) BMI charts.

Unfortunately, charts based on Caucasian populations are being used all over the world because they have the WHO stamp of approval.

-

Mark, thank you for contributing that very useful input.

I'm particularly interested in what you say that "charts based on Caucasian populations are being used all over the world because they have the WHO stamp of approval." I am bewildered that countries with mostly non-Caucasian populations should be using statistics based on mostly Caucasians.

and

"80% of the children / teenagers I was able to sample fell below the 25th percentile on the (age and sex appropriate) BMI charts."

Your comment alerts us to how using maths to predict healthy weight in non-Caucasians is even more misleading (than the example I give here). Thank you.

Would you agree this adds to the plea to use every tool at our disposal to assess someone's physical and mental state, rather than rely on maths? I hope I made this clear in this post but I'll check it over. I wouldn't like to give the impression that charts on their own give precise predictions. Did you see I also created a YouTube on the subject very recently?

-

-

Eva, excellent article and you're spot on. I found this article originally via Ref 100 on page 64 of your book (2020 edition).

While I have zero argument with your position on the median being an inappropriate target, the rest of your article seems to focus only on one side of the error – children who should be ABOVE the median.

You hardly discuss the other half of the problem i.e. the children who have been at, perhaps, the 10th (BMI) percentile all their lives but who are now being forced up to the 50th percentile.

This is particularly a problem for children whose families are naturally small – for example, children of Indian or Singaporean or Japanese origin.

Yes, the median is the halfway point. But if it's wrong for (approx) 50% of children, then it's wrong for the other 50% as well 😉

It would be great if you added some content on that. Many thanks.

-

Mark, you are spot on. Thank you for raising this. I'll see where I can tweak the article (I am cautious, as some of my visitors suffer from an ED and they may be quick to jump on any reason to avoid gaining weight).

For visitors reading this I'll explain some more:

I've not made a big deal about the 50% of kids for whom the median BMI might be an over-estimate. This is because:a) it won't do them any harm to have a buffer or to overshoot. It may indeed be helpful. (I write about this in https://anorexiafamily.com/weight-restoration-eating-disorder ).

b) as there is a tendency towards 'fat-bias' or 'fat-phobia', my guess is that many of these children will not be brought to a median BMI anyway — everyone may be quite quick to point out that the family norm is for a slight build.

Yes the sampling behind these BMI charts may well have been a mostly white-Caucasian population. I have only glanced at some of the papers explaining how some of these charts (in the UK, or CDC, or World Health Organisation) were compiled. I think the information is out there, for someone who has the patience.

What you've highlighted is one more reason to be very cautious with predicting recovery weight, and even though it might feel 'scientific' to plot an individual chart, it's never the only criterion for weight recovery.

Thanks for writing!

Eva

-

-

Thank you for this really important article Eva. As a clinician, I strongly believe that target weights for the purposes of eating disorder care and as a marker of “recovery” is a very dangerous tool.

I love your explanation of this for our care of children and adolescents with eating disorders.

Too often, the 50th percentile is just not the best benchmark for good physical or psychological recovery; and for a young person, and their family, the destructive nature of achieving this and then having the goalpost change can have a terrible impact on engagement in treatment, trust and recovery.

A few kg/pounds sometimes makes a huge difference in overcoming the eating disorder; and we don’t know why! Being at a higher percentile is for many, physically optimal for the body to return to functioning well.

We aren’t all built the same! Achieving the 50th percentile for weight is as absurd as insisting that the 50th percentile for height will be good enough and a measure of recovery!

Thank you for your work,

Dr Sarah Wells, Clinical Psychologist

-

Dear Dr Sarah Wells, thank you so much for taking the time to write this. The more clinicians speak up, the more it will become unacceptable to use arbitrary benchmarks.

Eva

-

-

Thank you, Eva, for writing this blog. My 11 year-old daughter’s (non-ED trained) physician told me when my daughter reached the 50th percentile that she was weight recovered and any existing angst/anxiety was who she was and that we were basically done. I had read otherwise and kept pushing as I knew she was still struggling immensely in a way she had not pre-ED. My daughter did not reach a good state / weight until a full 25 lbs later and a return to her historic growth curve at around the 85th percentile for weight for her age. That was just under a year ago and my daughter is now a healthy and happy 12 year-old rocking her curves and not looking back.

-

Thanks so much for taking the time to comment, Anna, it's been most useful. Parents and therapist need to hear about something like 85th percentile being right for some of our kids, and the arbitrariness of that 50th percentile mark.

-

LEAVE A COMMENT (parents, use a nickname)