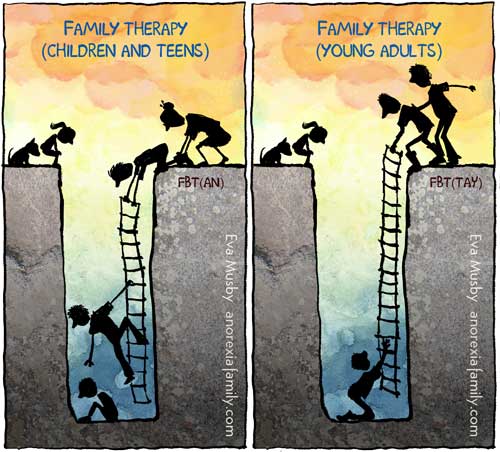

FBT-TAY: treatment that uses the power of parents on young adults

Is your child a young adult and you're looking for good anorexia treatment? Perhaps you've heard of FBT-TAY, and adaptation of Family-Based Treatment (FBT) for 'Transition Age Youth'. Perhaps you know about FBT, and how you can actively support challenging tasks of eating disorder recovery. Perhaps you'd like your adult child's current therapist to include you, because you know it doesn't work when your child is made to 'take responsibility' or 'take ownership' of one terrifying meal after another.

Well, FBT-TAY treatment is an attempt to use hands-on support from parents while also giving the young adult space to collaborate and have some buy-in. I'll describe here aspects of the approach that might be useful, and those that were perhaps responsible for the trial to show poor results.

And I'll quote from certified FBT therapist Kellie Lavender, who told me that it's very gratifying to use FBT-TAY with young adults. She's seen it work:

"If an older adolescent/young adult agrees to have their loved ones involved, this is a treatment model that can and should be offered as an option."

Lauren, one of her 23-year old clients wrote:

"My anorexia recovery started with individual treatment but I got stuck and I was

not improving after 2 yrs.I changed to FBT-TAY. It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever faced. Surrendering the anorexia control and letting my family take over felt terrifying at the start.

But I'm so grateful now, because FBT-TAY gave my family the tools to support me when I couldn’t support myself, laying the foundation for true healing, 100%

recovery and a life more meaningful than I ever imagined."

When parents are pushed away

We're in this crazy situation where as soon as someone turns 18, treatment dramatically changes. The helpful principles of a family-based approach (FBT or similar) get discarded.

The strength of a family-based approach is that parents walk alongside their child to make meals and weight gain possible, in spite of how anxiety-producing this is. And it's not just meals: parents accompany their child to transform eating disorder behaviours back into life-enhancing ones, to go from rules and restriction to a rich life.

But now, your child is 18! Their clinician hasn't been curious to learn, from their colleagues in adolescent services, of the huge progress made since parents were made part of the treatment. The patient is an adult, so it's only healthy to develop independence from parents, right? If parents and partners are considered at all, it's to train them to manage their emotions so as to avoid doing harm… and to mostly stay out of the way. The thrust of treatment is: every week we talk for 1 hour, and you are to take responsibility for achieving change all by yourself for the remaining 167 hours.

Therapist Kellie Lavender strongly argues against this sad situation:

"Trials of FBT for anorexia have focused on ages up to 18, but this does not

mean that it cannot be applied to older clients, only that we do not have evidence

(yet) of its effectiveness. There have been case series of FBT-TAY (for young adults), and the approach would be considered a novel treatment at this point.

Because I see FBT working for many, if not most, families, it makes sense to me

to use this model with young adults who still live at home and are open to having

their parents involved in an active role.

International guidelines encourage involvement of parents and loved ones with all

adult treatments, at all ages anyway."

What better models are there when someone turns 18?

Treatment for adults really has to improve, and on my page on adults I introduce you to some very hopeful models where parents or partners or friends are roped in to give effective, practical support.

Here I'll focus on the FBT-TAY model, developed for young adults.

FBT-TAY is Family-Based Treatment for 'Transition Age Youth'. It's an adaptation of the usual FBT treatment, and trials were done on ages 17 to 25. It aims to use the good stuff of FBT, but with more buy-in from the young person.

Sounds hopeful, right? Maybe you've come to this page because you've heard of FBT-TAY and you want that for your young adult.

Sadly, when results for the study were analysed, what came up was … a fail.

So why even talk about it? Because it's as useful to know what doesn't work as to know what does.

And… because a therapist can make it work, as you'll see from my messages with Kellie Lavender. It may take a while, though:

"FBT-TAY has a ’slower burn’ in the beginning, unlike traditional FBT."

On this page I summarize the method. And I will give you my personal opinion on aspects which might be worth keeping, and aspects which to my mind, are weaknesses that are worth ditching. It's all opinion, because there are no 'dismantling' studies to indicate which aspects of FBT, or of FBT-TAY, are particularly effective and which make recovery harder.

FBT-TAY: an adaptation of a well-established treatment for teens

FBT-TAY (Family-Based Treatment for Transition Age Youth) is an adaptation of FBT for anorexia, the recommended treatment for anorexia or bulimia for age 12 to 18.

FBT: Family-Based Treatment, tested age 12 to 18

FBT-TAY: for Transition-Age Youth, tested age 17 to 25

Yes, the FBT studies included 18 years old. If FBT is not made available to 18-year olds, it's because of treatment providers split their administration by age, not because anyone has demonstrated that the FBT studies were wrong in including 18 year olds. Indeed the top experts choose their method according to the person's needs and capabilities and support systems, not according to age.

* Link: Family therapy for eating disorders: what is FBT/Maudsley? *

The FBT-TAY variation comes from work on 17 to 25 year olds by Gina Dimitropoulos and Kristen Anderson, with James Lock and Daniel Le Grange. They report on it in the 2015 book Family Therapy for Eating and Weight Disorders shown below. I'll describe the essentials in a second. But first I'll tell you how it hasn't seemed to work that well.

Does FBT-TAY work?

After describing FBT-TAY in the aforementioned 2015 book, the authors published results of their study in 2018: 'Family-based treatment for transition age youth: parental self-efficacy and caregiver accommodation'

If I'm reading the results correctly, it found that sadly, the young person's symptoms or weight did not change. Meanwhile the parents became more confident in their ability to support their child and they perceived that they were engaging less with/or permitting fewer ED symptoms. This is in sharp contrast with FBT for 12-18s, when parental 'self-efficacy' really does correspond to kids getting better.

This reminds me that whenever I've seen research on 'New Maudsley' (careful, in spite of the name it's very different from FBT/Maudsley) the published outcomes are about how the parents feel better… but I haven't seen any corresponding investigation in any changes in the patient's symptoms.

The FBT-TAY authors wonder if the weakness of the approach lies in its focus on collaboration between parent and youth, and on working towards the person's autonomy and re-integration into ordinary life. In other words (my interpretation), too much negotiating, and too much freedom, too soon. I'm sure that Gina Dimitropoulos and Kristen Anderson, who are super-experienced certified FBT therapists, have made many more discoveries over the years. Indeed I'm glad to report that Gina has just given this page a big thumbs up.

But let's not dismiss the potential of FBT-TAY. For therapist Kellie Lavender, it can be made to work:

"Working with young adults between 17 and 25 using FBT-TAY has been some of the most gratifying work I have done. I have seen it work."

I will now summarise for you the main elements of FBT-TAY. I'll add some of my own comments to help give you ideas how you might make use of some parts, and let go of others. Again, it's just ideas — we don't have the research to tease this out.

How does FBT-TAY differ from the regular FBT?

Kellie Lavender tells me that the key underpinning principles are the same. Key modifications of FBT-TAY are:

- It is tailored to address the unique developmental needs of older

adolescents and young adults with AN. - It promotes greater collaboration with the young adult and their parents to

work against the illness together. - It assists with psychological tasks and changes associated with emerging

adulthood in the final phase of the treatment.

FBT-TAY requires some buy-in from the young adult

Central to FBT-TAY is a level of buy-in from the patient. The young adult has to be willing to have their parents support them with eating for as long as they are not able to make changes by themselves. Imagine that. You’re 22, you are in the grip of anorexia, which is an illness that makes your brain react with extreme fear and disgust to eating and weight gain, and you have to find the courage to ask your parents to help you eat and gain weight. This buy-in work is done in individual therapy, after which parents are brought into the conversation.

From therapist Kellie Lavender:

"I think what makes the difference is the skill level of the therapist to ‘dance’ the line of engaging with the healthy part of the young person, knowing anorexia very well. This gains the respect of the adult, while empowering the parents at the same time with collaborative problem solving.

I see that when they make progress and they feel understood, the adult becomes much more engaged in the process."

While children and teens with anorexia tend to be deep into the illness, people who have been ill for a while can be moments of motivation. While their drive to restrict is strong, they also realise that their life has become a mess and that they need help. This could make your young adult collaborate in ways that tend not to exist with children and teens.

Still, you can expect young adults to be ambivalent around recovery, or to flip into wanting to do it all by themselves before they have the capacity to do so.

So a big task of the FBT-TAY therapist is to work on maintaining the willingness of the young person to collaborate. This is quite different from FBT, where we don't expect our children to agree to work with us, and we manage to support them in spite of their resistance.

Therapist Kellie Lavender told me:

In individual sessions with the young adult, I discuss the week, help them better communicate with their parent, assist them with goals and with strategies for anxiety. I empathise with their struggle and hold hope and motivation for recovery.

I marvel at the skill of a therapist in doing the ground work to maintain teamwork. And in doing it again and again. Indeed Kellie Lavender said, "The task of the therapist is to empower both the parents and young person to work against the anorexia together. This ‘dance‘ requires a level of therapeutic expertise that, importantly, the clinician must learn and develop. It is probably a key aspect that distinguishes FBT-TAY from FBT for adolescents."

In other words, you need an excellent, experienced therapist.

How you might adapt this

Should we try this at home if we don’t have access to an FBT-TAY therapist? Adults to report coming home for their parents' help — how it was hard but it turned them around.

I know I would do all I can to be hands-on, because I remember how meal support turned my daughter around at age 10, and then again at 15. And I also know of many parents who have done this with their university-age child with minimal outside help. And, it must be said, with only small and unreliable amounts of buy-in from their young adult. Sometimes all you know, as a parent, is that you will do the very best you can to support the very next meal. When something is truly scary, as meals are for our children, sometimes you can only get buy-in for the next mouthful.

‘Here’s dinner’: parents and young adults on the same team

With FBT-TAY the therapist is constantly working to ensure parents and young person think of themselves as on the same team.

Collaboration means that the young adult is not expected to direct their own recovery (the same as for younger people), but then neither are the parents expected to take sole responsibility for their son or daughter’s eating (whereas with younger teens, parents are given that responsibility). All the same, parents are expected to make a commitment to help their child gain weight and normalize eating. The details of how that is done are worked out collaboratively with the therapist’s help.

For instance the family may note that the young person has not been handling meals well or that shopping or cooking are an issue, and all may agree that the parents will take over these tasks. Contrast that with a child or teen in the early part of FBT treatment: parents quickly learn to keep their child out of the kitchen and to support all meals whether their child likes it or not.

In FBT-TAY, just like in FBT, parents are empowered to use their expertise to best support their child through the distressing work of recovery. If the illness has been dragging on for years, therapists have a big role in supporting burnt-out parents. If the illness is new, then parents need to skills they never needed before — this is what all my resources aim to do.

Teamwork does not mean parents are included in everything: young adults have some individual sessions with the therapist. Contrast that with FBT, where all sessions are with parents, because they are in charge of delivering the treatment.

The risks with individual sessions is that communications can get distorted (“The therapist says you give me too much food and that I don’t need to gain any more weight!”). A good clinician will take care to avoid this pitfall. As for siblings being included in sessions, young adults can decide what they prefer, whereas with children and teens the norm is to include the whole family.

How you might adapt this

It feels so right to include one's child in teamwork, to collaborate with them, to give them ownership. But this is anorexia. Usually there is a long period during which the person just can't do it. Their mind isn't functioning that way. Food is terrifying. Excessive exercise and other purging methods might be the only thing that brings temporary peace. Worse, going against eating-disorder restriction induces massive guilt and distress.

With all that, I think parents have to become their child's surrogate wise brain. To make the decisions their child doesn't have the capacity to make. Collaborate on anything your child can bring their wise self to, and bring strong decision-making and practical support to everything else. If this horrifies you, note that a hospital takes away a lot more of a person's autonomy. As nutrition and weight gain kick in, you'll keep re-assessing, as your child will be able to do more.

The young person tracks their eating… or not

In the trials, during the first phase of treatment, when young adults really needed support to eat, they were asked to keep note of what they ate, when they ate, who they’re eating with, and what helped or hindered their eating.

Reading this will make many parents of children and teens shudder. Keeping track of food eaten is how our youngsters count calories, obsess, beat themselves up, and resolve to observe even more draconian standards next time. Keeping track is an anorexic behaviour we try to turn them away from. We promote other interests and prompt our children to get on with the good stuff of life.

With FBT-TAY the idea behind food records is for young people to be more aware of eating patterns and of ways to seek help when they are struggling. It is typically done in a way that does not encourage calorie-counting. They are encouraged to tell their parents about what they’re finding difficult. Of course this kind of discussion happens in therapy with younger teens too, but without the record-keeping.

How you might adapt this

Now please remember that FBT-TAY studies do not demonstrate huge success rates. If I were to look for adaptations, I think I'd get rid of the food tracking, at least during the fearful and obsessive early months of renourishment. When I recall adults describing how they got well with the help of their family, I don't think they tracked their food. They 'just' ate.

Food tracking is really not necessary (or useful)

Given how uncomfortable the idea of food tracking makes me, I was glad to hear from therapist Kellie Lavender that in her sessions, "The job of tracking food still lies with the parents. But we agree upon the pace in joint sessions." And yes, parents are there during meals — it's active support.

Moving on to independence

After a few weeks, parents and patient work out how best to gradually hand control back to the young person. When this happens is a collaborative decision, and it may happen sooner than with a child or younger teen, since young adults can’t re-engage with a good life until they get back into studies or work. Their journey to independence, studies, work and intimate relationships may have been disrupted by the length of the illness.

FBT treatment ends with a few sessions ('Phase 3') attending to the child or teen's normal development now that the eating disorder has stopped interfering with their life. This is done in FBT-TAY as well.

How you might adapt this

If it was my child, with all I know, I would be really cautious about giving too much independence, too soon. I'd be worried about the young person getting such a strong say in when parental support should stop. Yes, life calls — work, university. And developing a life worth living is part of the treatment. But with FBT in teens, too often the handover of independence is done too suddenly, too early, without enough coaching, without enough risk assessment. This is causing too many 'relapses' (I use quotation marks because it's not a relapse if treatment was never properly completed).

I say more on this here: Phase 2: how to guide your child to complete recovery from an eating disorder. If you are helping a young adult, see if some of what we know for teens can help you with your son or daughter.

And there's something else that might help you be more effective. It's not often spelled out that for complete recovery, at any age, the fears and eating disorder behaviours and rituals need to be extinguished. You don't want your young adult to go back to university avoiding carbs, or over-exercising, or counting calories. Keep them at home a while longer while you help them through exposure work. More from me on this in Chapter 9 of my book, many of my Bitesize audios, and I do a workshop on this too.

Relapse prevention plan

FBT-TAY includes work on a relapse prevention plan. What are the risk factors, what are the signs of relapse, and how will the young person seek help from parents or others? The young person works on this with the therapist first, after which parents are involved.

This contrasts with the FBT manual, where only a little time goes into planning for future challenges such as college or work. There isn’t much focus on relapse prevention, presumably because the child or teen is expected to be at home a while longer, and the parents will pick up signs of relapse before things go too far. Besides, as far as we know, most often there is no relapse. Still therapists use their judgement and whatever the patient’s age, they can give plenty of support around planning for relapse prevention.

How you might adapt this

If you're not getting the help of good clinicians, you might be daunted at the idea of a relapse prevention plan. In my book I discuss measures you can put in place as your child leaves the nest, and I give quite a few links to help you with relapse prevention planning. You can also Google what therapists Sarah Ravin and Lauren Muhlheim each write about relapse prevention plans.

How about other eating disorders?

Given that eating disorders like bulimia or binge-eating disorders are very common, it is shocking how little research there is to report on. The FBT-TAY study I’m telling you about here is specifically about anorexia, though I imagine it is pretty safe to assume it is relevant to other restricting eating disorders that may not quite fit the official anorexia diagnosis. In particular, the diagnosis of 'atypical anorexia' should be treated as just 'anorexia'.

For teens, Family-Based Treatment for Bulimia Nervosa (FBT-BN) is already quite collaborative. That's because adolescents with bulimia are likely to have both the motivation and the cognitive ability to get well (they hate that they binge, and they hate that they purge). So presumably it's not a big stretch to use FBT-BN principles with a young adult. Do check out, also, CBT for eating disorders if your young adult has bulimia or binge-eating disorder.

Finding an FBT-TAY therapist

FBT-TAY is not widely known. I think all that's happened is that a team of FBT therapists experimented with a new protocol for treating young adults. So if you want the exact approach, then I suspect you'll need to seek out one of the authors. And I suspect that by the time they see you and your child, they will have ways of improving on what they described in their researchy.

I would hope that any well-qualified FBT therapist would adapt treatment, any age, for any individual, to make good use of parents. Ask around. and check my page on adults.

More on related topics:

* Adults or young adults: treatment for a restrictive eating disorder *

* Certified FBT therapists who Zoom world-wide *

* Family therapy for eating disorders: what is FBT/Maudsley? *

* Weight-restoration: why and how much weight gain? *

* How to choose treatment for your child with an eating disorder? *

LEAVE A COMMENT (parents, use a nickname)