So many questions on weight gain and healthy weight!

This is my main page on weight restoration. I'll explain:

- why restoring a healthy weight is absolutely necessary to treat an eating disorder and… it's not sufficient — there's work to do, in addition to weight recovery

- if you know how much weight was lost, usually that's an absolute minimum that needs to be regained.

- weight has to increase to match a young person's need for growth

- if a recovery weight or weight range is announced (and I give pros and cons), it can only be a rough estimate

- when predicting a recovery weight, most clinicians use only a few of the recommended criteria for assessment: I explain the methods most often used and why some predictions can be very wrong

- you can't pronounce someone is weight-recovered just because they've reached a predicted goal weight: if they still have issues with their physical or mental state, there is uncertainty on whether more weight, more work, or more time are needed.

- how you'll need to experiment with weight and more work and time if your child is 'stuck'

My overall message will be for you to focus on the tasks of recovery. Accept the uncertainty about the weight range that will eventually prove to suit your child.

* For a list of more of my posts on the topic of weight, jump to the bottom here *

Why does weight matter?

"If you don't get weight restoration, you will get nothing"

Dr Julie O'Toole in YouTube "What constitutes good medical care"

A healthy weight is necessary for recovery from an eating disorder. Without a healthy weight, the eating disorder will stay. A healthy weight and body composition are necessary for the wellbeing of the body, the brain, and the mind.

"Behavioral recovery follows physical recovery, and psychological recovery follows behavioral recovery"

Dr Alix Timko in the excellent webinar 'Challenging Parent Perceptions on Weight, Fat, and Food'

Think of healthy weight like a healthy amount of moisture in your house plant. My azalea loses all its leaves if I don't water it enough. My azalea has other needs but it certainly needs water.

Another analogy: regular food, and getting back up to a healthy weight, are essential medicine.

"Attainment of appropriate body weight in anorexia nervosa is a critical element of full recovery. A person can be insightful, motivated, successful, and doing better than they were before, but unless they have achieved full weight restoration, they remain at medical and psychological risk and aren’t well. This is pretty well accepted."

Dr Jennifer Gaudiani, internist and expert on the medical complications of eating disorders, in 'Weight goals in anorexia nervosa treatment'

"[Insufficiently high] BMI at the end of treatment is a predictor of relapse"

Frostad et al (2022) – from review of almost 1400 anorexia patients

In the Frostad review quoted above, having a BMI at the lower end of the 'normal'/'healthy' BMI range was the strongest predictor of relapse. Weight needs to be higher.

A healthy weight is not a designer choice but a biological imperative.

"Weight gain is key in supporting other psychological, physical and quality of life changes that are needed for improvement or recovery"

NICE guideline for eating disorders (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence)

"Like other medical indices (blood pressure, heart rate, etc), weights are medical indices"

NICE guideline for eating disorders (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence)

If your child has been restricting (whether because of anorexia or another eating disorder — or indeed, any illness), their weight is not where nature intended. They must recover lost weight, plus catch up with lost growth, plus keep growing. Just like shoe size, weight has to go up when you're a child or adolescent and even a young adult.

By the way, I mentioned 'body composition' because healthy weight gain does not mean just gaining muscle. Body fat isn't just padding: it has an active role in our body, including the production of essential hormones.

Recovery weight, goal, target, healthy, ideal, optimum: definitions

We're talking here of a weight range that in hindsight, proves to suit an individual well. They feel good in that range, physically and mentally.

Professionals use different words to refer to roughly the same thing: target weight / recovery weight / weight restored / healthy weight / ideal weight / optimum. It's always worth asking a professional what they mean, though. For instance, a goal weight might be an intermediate goal, a staging post. I'll say more later on how you communicate with your child about these concepts.

The weight nature seeks

How biology determines a healthy weight [Click]

"There is considerable evidence that our weight is genetically influenced. Research suggests that our minimum weight cannot be significantly altered over the long term. This hypothesis is called 'set-point theory'[….] The aim of any treatment has to be to help [patients] to live and eat more healthily. This means helping them to eat regular healthy meals (which might or might not lead them to put on weight) and, if they do gain some weight, helping them to accept this weight as the one that they are 'meant to be' (wherever it may be within the healthy BMI range)"

Glenn Waller et al in the CBT Manual 'Cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders'

You can read more on set-point theory here. In general, from what we see of adult dieters, people tend to revert to their previous highest weight. There isn't much science to explain if this is due to genetics, or biology, or psychology, or eating habits, or a mix of all those.

With our children, regaining lost weight usually is required, plus whatever weight a child that age usually gains in normal growth. That's a very rough starting point for those who want a sense of the feeding work ahead.

Consider an optimal weight range as one that is conducive to physical and mental health. In adults that have stopped growing, it's also a range that is effortlessly stable when people eat flexibly to their appetite, without restricting or bingeing. Having said that, human beings are highly variable, and some don't have the ability to detect or follow appetite and fullness cues, so again, we face uncertainty regarding their normal weight range.

Regain weight… now!

"During the early stages it is generally entirely appropriate to be focused on the need for weight gain."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley's Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication, 2019

Why you should get on with it — worry about a target later [Click]

It's a no-brainer. If your child has been restricting, they need to gain weight. Don't waste time wondering 'how much'. Their body is in famine mode. It needs nutrition and weight gain. Start regaining what was lost. If you have no idea how much was lost, a good eating disorder clinician will still prioritise weight gain.

Weight gain is, obviously, needed for physical repair, but is also essential for the mind (see for instance Accurso et al's study 'Is weight gain really a catalyst for broader recovery?' and Dr Sarah Ravin's plain English summary of it.)

While it might seem sensible to go 'slow and low', a lot of research indicates best results come with rapid gains, reaching full weight recovery. (See references at the bottom of this page.)

"It is well established in outpatient and higher levels of care that early and steady weight gain is associated with good prognosis"

AED Guidebook for Nutrition Treatment of Eating Disorders (2020)

So, start renourishing.

This isn't just for anorexia, and this isn't just for low-weight individuals. With an eating disorder, including bulimia or binge-eating disorder, there is usually a component of restriction. If someone has lost weight, or failed to grow, they need weight gain. Also, all eating-disorder sufferers need regular renourishment, whatever their weight or body shape.

The only reason not to renourish fast now is if your child is at risk of refeeding syndrome. Check with a professional. (What's normally meant by 'fast' is half a kilo to one kilo a week at home, and usually twice as fast in an inpatient setting — more on this in Chapter 6 of my book.)

If your child used to be labelled as 'overweight', or still is, it makes no difference: their health needs to be checked and if they lost weight they now need to increase it.

"I do not know how many times I have been told by a parent that their pediatrician dismissed their concerns about their child’s weight loss as 'not a problem' because they were 'still on the normal BMI chart.’"

Julie O'Toole, Chief Medical Officer of Kartini Clinic in The misuse of BMI in diagnosis of pediatric eating disorders

Some treatment providers like to estimate a goal weight very early on. I'll discuss pros and cons of you and your child being given any kind of number. What is sure is that a goal weight is no better than a weather forecast, and must not be a criterion for treatment ending. When your child reaches the predicted number, they may be well, or they might need more gain. They certainly will need to continue work on their habits, behaviours and fears.

Weight restoration: essential but not sufficient for recovery

"Although weight restoration is a goal for FBT, it is not sufficient. If weight restoration was sufficient for treatment of anorexia we would have cured it along ago."

James Lock, co-author of the FBT treatment manual, personal communication, 2019

An analogy: my azalea absolutely needs water, but that's not sufficient. It needs the right soil, and the right pot. I've had to experiment with different locations in the house too.

Another analogy: there are medicines we take to get over the worst of an illness — like an antibiotic after surgery. After that, treatment continues and there may be rehabilitation work before someone is back to their 'normal'.

When 'recovery' weight is set too low

There is no such thing as a universal minimum target weight. People vary dramatically in terms of body build, muscle mass, bone structure, body shape, and natural weight […]Many patients are left to struggle with ongoing depression, fatigue, anxiety, and preoccupation with food and weight because they haven’t reached their optimal body weight.

Dr Sarah Ravin, in 10 Common Mistakes in Eating Disorder Treatment

How a low weight target will keep your child stuck [Click]

Weight is a bit like shoe size: there's a size that fits your child, and it's probably different from their friends' shoe size. It could be smaller than average, or larger. Sure, there's a little more flexibility with weight than with shoe size — we're taking about a range rather than a number — but every respected expert I can think of will tell you one can't beat an eating disorder with 'too small'.

And just as we don't expect our shoe size to go down, we don't expect people with an eating disorder to function well when weight-suppressed.

"There are certainly people who get stuck in the recovery process at a weight that is too low for them."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley's Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication, 2019

For some more analogies, consider that for some health conditions, you need the right dose of medicine. Stopping antibiotics early is problematic. And back to my azalea: buds will keep falling off if I under-water it.

Therapist Lauren Muhlheim asks 'Are we setting recovery weights too low?' here (and pretty much answers, 'yes'). Likewise:

"It is clear that under-nutrition cannot be good—yet as practitioners, many of us contribute unintentionally to this mistake every day. How so? By allowing patients to remain slightly below a weight that represents real physiologic restoration for fear that they will not be able to tolerate the anxiety of returning to a “non-skinny” weight/BMI.

Julie O'Toole, Chief Medical Officer of Kartini Clinic, in 'The dangers of staying slightly below weight'

With a family-based model, we don't need buy-in from our children. We support them to eat, meal after meal, in spite of their fear. With time and weight gain, their resistance to weight gain usually reduces as they experience that they look and feel fine.

Note that it's normal for anxiety over body shape to spike every now and again, but it abates as people are supported to push through. In particular, there may be anxiety a few kilos before weight-restoration (see Dr Anna Vinter's article about this phenomenon, which some refer to as the 'extinction burst') where it's particularly important to keep going.

"The anxiety over being fat is more likely to significantly improve with recovery, more regular eating patterns, and — ironically — weight gain than it is with appeasement."

Lauren Muhlheim in 'When your teen has an eating disorder'

"There is another powerful belief that makes some parents wary of 'too much weight gain' — the belief that their child will become distressed, more depressed and 'worse psychologically' if they 'gain too much'. There are some providers out there who share this belief as well, setting weight gain goals 'their clients can accept'. The fallacy to this argument is that we are not talking about the average child or teen, we are talking about the one with anorexia nervosa. There is quite literally no weight, however low, that will placate an eating disorder."

Julie O'Toole, Chief Medical Officer of Kartini Clinic, in 'Setting goal weights'

Further down, in 'The abandoned underweight', I'll talk of the outdated practice of deliberately setting low weight targets.

"I’ve found that the single most important variable—the safeguard that separates the valley of recovery from the valley of illness—is maintaining the weight range that’s right for me[…] A few pounds [down], it suddenly felt more comfortable to be hungry than full. A meal that seemed normal two weeks ago looked huge and daunting."

Emily Boring, in an enlightening piece 'When in doubt, aim higher: What I wish I'd known about target weights in recovery' Listen also on this podcast

But my child is horrified of weight gain

Have a read of this, as it's pretty typical [Click]

"Paradoxically, I became freer from preoccupation with weight and food when I allowed my weight to climb higher […] I can eat and move on with my life much more easily than even just a handful of pounds lower, and I don’t constantly have thoughts of food and weight and exercise on my mind.

Hannah, in the excellent piece Insights from relapse to recovery: what I’ve learned from falling and getting back up again

Clinician and researcher Alix Timko has a great graph in this excellent YouTube, where she says:

'It's very counterintuitive but as weight goes up these things [measures of shape and weight concerns and of various eating disorder thoughts, beliefs and behaviours] go down, and super fast… [Even though] we are not directly targeting these cognitions.'

Here's a graph from myself:

Weight isn't a designer item

When females in China were tortured to make their feet small, I imagine the shoe shops only stocked torturously tiny shoes…

I have used shoe size as an analogy for healthy weight, and of course, weight is a little more adaptable than shoe size. Most of us are comfortable within a range of a few kilos. Within this zone, we eat freely and our body has stability and health.

But we're not that adaptable. Diet companies have told us for years that we can manipulate our weight to enjoy a fashion-driven body shape. We know people can get there, but in spite of willpower, rarely does their body let them stay there.

Why this weight? Genetics and biology

"The major determinant of body weight is genetic"

AED Guidebook for Nutrition Treatment of Eating Disorders (2020)

Click for more

We are now seeing anorexia through a new lens, thanks to ground-breaking research into the genome, first reported on in 2019 . The Anorexia Nervosa Genetics Initiative (ANGI) found that the illness has a metabolic component. The study leader Dr Cynthia Bulik reported on this:

"One very important message is how critical it is to adequately renourish people with anorexia nervosa — especially in the United States, we often see that insurance companies will de-authorize treatment prematurely. So people will be discharged from the hospital before their bodies have had an opportunity to sort of re-equilibrate or stabilize at a healthy weight. And so this suggests that getting the metabolism stabilized again might be a very important — in fact core component — to recovery from anorexia nervosa."

Why do bodies and brains malfunction below optimum weight? This is still the topic of research, but here are some hints. Muscle and body fat aren't just inert things. They have functions — metabolic and more. Body fat is a hormone-producing organ. Minimising fat is as daft as disabling chunks of your liver or gut. Think of how female athletes can become so unwell and lose their menstrual cycle when their body weight — and estrogen level — drops too much.

Another example from a case study: the Minnesota starvation experiment ended with men experiencing extreme hunger, which it seems abated once they regained their body fat.

One more example: an important hormone produced by our fat cells is leptin. Leptin plays a role in the complex pathways that drive our appetite and eating behaviour. Below some threshold, low leptin seems to bring on the starvation response we are familiar with in anorexia: this may explain the hyperactivity, low mood, and distorted beliefs that our children suffer from. These issues tend to reduce as we increase body weight, possibly because leptin then rises too. Frustratingly though, there is a lag between the two. Leptin doesn't rise quite as swiftly as body fat does. This is yet another reason not to expect weight recovery to immediately bring mental recovery.

The extent to which all these mechanisms respond to body weight varies greatly between individuals. Genetics is a huge factor.

The take-home message is that individuals vary, and the help they get must be individualised. It is not OK to give one-size-fits-all targets. And parents, professionals and recovered people must be really cautious about turning individual experience into standards for all.

How to work out an optimal weight range

First, I'm going to disappoint you: there is no 'working out' of optimal weight — at least, nothing can be predicted with a great level of confidence or accuracy. Human beings are complex, and we just don't have the science to predict precisely what will suit them. The only certainty for almost everyone is, regain lost weight as an absolute minimum, then keep assessing how much more is beneficial, as explained later.

Use any weight goal a bit like a weather forecast. An expert has done their best with the many variables, but ultimately, you'll only know it's sunny tomorrow… when tomorrow comes.

If tomorrow turns out to be wet, then you'll cancel the beach trip. It is poor treatment indeed when a clinician decides your child ought to be well now, just because they've reached a predicted recovery weight.

Given that many clinicians do 'set a recovery weight range', you need to know that some methods are better than others. The key is that the estimate must take into account your child as an individual. Later I'll show you how you might instead be given a one-size-fits-all target.

How an optimal weight range is worked out for each individual [Click]

The following provide clues to help predict a healthy weight range:

- height and weight before disordered eating began

- the extent of weight loss, or failure to gain weight or height

- growth history (height, weight, BMI) plotted on a percentile growth chart (but as I'll show later, this is still a poor tool)

- menstrual history

- current pubertal stage (which will help factor in growth spurts)

- bone age (e.g. through X-rays)

- photographs

- genetics (based on the build of family members)

- skeletal frame

- muscle bulk (muscle weighs a lot, and health requires body fat too)

- and importantly, the mental state: whether the eating disorder mindset is still as strong, or easing off.

(For some references to the above, see for instance the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Guidelines (2023)

"A person’s healthy weight is highly individual to their genetics, their medical history, their experiences with food and dieting/caloric restriction throughout their life, and their body’s unique responses to inadequate fueling and to nutritional rehabilitation."

Dr Jennifer Gaudiani, internist and expert on the medical complications of eating disorders, in 'Weight goals in anorexia nervosa treatment'

"A “biologically appropriate weight” is a weight that is easily maintained without need for dieting or inappropriate food and exercise behaviors, and reflects pre-morbid weight, normal physical and psychological function, genetic predisposition ethnicity, gender, and family history"

AED Guidebook for Nutrition Treatment of Eating Disorders (2020)

"Weight has to be determined on an individual basis"

Daniel Le Grange, co-author of the FBT manual, in this webinar

"For adolescents and young adults and adults, we are really trying to think about their lifetime growth trajectory and not just some standard norm, off a chart. So we're looking at their growth patterns throughout their own lives, considering what pubertal stage they're at, considering if catchup height is needed"

Rebecka Peebles, FEAST of Knowledge 2024 conference

Notice that the list of physical signs if long, and few clinicians will consider them all. If the only physical signs considered are normal heart rate, pulse and labs, and return of menses, then that's usually insufficient to signal weight recovery. So it's important to also assess mental state.

How mental state guides the search for a recovery weight

When trying to work out if your child is close to weight recovery, a good clinician will not only look at physical signs. They'll also take into account your child's mental state.

That's because weight and mental state are related. The strongest demonstration of the weight-state relationship is when someone loses weight. Many observe that there is a threshold — a tipping point — below which eating disorder thoughts are activated.

Click for more on this

How about going the other way, starting from underweight? Well, it's not quite symmetrical. Renourishing and weight gain past the tipping point rarely bring complete recovery. They do usually bring gradual mental improvements. And some parents may go from one week to the next, delightedly saying , 'My kid is back!' so in that sense, they see a tipping point.

But full mental recovery takes more work than just raising weight. Once someone has an eating disorder, usually they need weight recovery plus other work, as discussed further down.

Still, we expect a healthy weight to bring significant mental improvements. So if your child is still highly distressed by food, desperately trying to exercise, very delusional, showing big levels of resistance or aggression, then a clinician may sensibly guess that they are still significantly underweight.

Other methods, and why there are huge differences

Above, I listed the factors that help predict an optimal weight range for any individual. Not many of you have access to a treatment team with expertise on all of those.

What you're likely to get from an eating disorder clinician is one of two methods:

- A one-size-fits-all calculation: a dangerously blunt statistical tool that produces an underestimate for half the population.

- or extrapolating from a growth chart: a far better method, but you should still understand its limitations

I'll describe the two methods here [Click]

Here's an overview of the two methods, and for more detail, see this other post.

The median BMI / percent weight-for-height method: awful!

Using median BMI is a bit like giving all girls of the same age the same shoe size. Or predicting the weather near you today based on the average rainfall worldwide.

It's good at telling you that someone is likely to be dangerously thin… and not much good at anything else.

The median BMI method doesn't feature in any of the reputable guidelines, yet it's still commonly in use. I think some clinicians don't realise that it's just a 'middle-size fits all' calculation, and that humans can't all be well in the middle. You'll know this method is in use if you're told your child should be at '100 percent weight-for-height' (or some other percentage). What that corresponds to is the median (or middle) BMI of a whole population of girls or boys of your child's age. Being the middle, it's going to under-predict healthy weight for half the patients, sometimes by a huge amount. Apart from your child's sex and age, there is nothing individual about it. I take you through this sorry method in this post and in this YouTube.

Using a growth chart: part of the picture

The other tool that is commonly used is far better (but is still very approximate when used in isolation): plotting growth history on a growth chart. I created this YouTube to show you how to use one:

The idea is to use your child's growth history to predict current and future needs. Past weight and height data are plotted on a percentile growth chart, and the assumption is that your child should track along the same percentile. I explain here how this can be wrong. For instance, as I say here, you can expect your child to have a growth spurt some time between their tweens and teens, and it could be big.

Using a growth chart in isolation is a bit like predicting your town's weather today based on previous years — without looking a current weather fronts.

Huge differences in predicted healthy weight

Overall, the weights or BMIs presumed to be 'healthy' and conducive to eating disorder recovery vary mightily from one treatment provider to another (as shown in this study by Roots et al, described in plain English by Tetyana in 'Setting a target weight: an arbitrary exercise?)

Why are we even talking about weight targets?

Some clinicians I respect say there's no need for a target weight. When they first see a child, it's usually obvious that weight gain is needed. Later, weight will only be one of many indicators of health. And of course a healthy weight is not a single figure but a range.

"Restoring physical health (which includes being at a weight that is healthy for that particular person) is a necessary condition of recovering from anorexia. However, that does not mean that we need to identify a particular weight to aim for as a target for recovery."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley's Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication, 2019

More expert views on this [Click]

"We focus on using the body's response to nutrition rather than a weight goal"

Lock and Le Grange, in FBT treatment manual

"While weight is one measure to use for judging clinical progress it is helpful to think of weight as reflective of a state of health rather than an end goal in and of itself. The healthy weight becomes that weight where a person is physically and mentally healthy."

Therese Waterhous and Melanie Jacob, Practice Paper of the American Dietetic Association (now the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics)

Here's a reason for not talking about target weight:

"Reliance on targets is often a mark of the illness' need for 'certainty'. Later on in treatment everyone understands that it is other areas of life that will determine when someone has reached a weight that is good for them."

Esther Blessitt,Principal Family Therapist at Maudsley's Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication, 2019

In other words, we don't engage in the eating-disorder's demands. Our poor children have an anxious focus on weight and they kid themselves that numbers will reassure them. Instead, we talk about health and wellbeing, and we help them to tolerate uncertainty. As they get well, they appreciate feeling good, they see that they haven't turned into a blob, and they loosen their attachment to a number.

It makes a lot of sense not to discuss target weight while someone is very underweight:

"It's not a topic that should even be discussed until well into the refeeding process. With a starved, paranoid cave person brain and a critical fear of even one pound of weight gain, no one should be tormented early in recovery by the idea of some number range they are supposed to reach, weeks or months hence."

Jennifer Gaudiani in her highly recommended book, 'Sick enough'

An argument in favour of a weight target

Now I'll give you a different view, from therapists I also respect, which is that weight goals have their usefulness. These therapists find it useful to discuss target weight in therapy.

First, it is part of exposure treatment for your child's fears around weight:

"By NOT saying the weight range target to the kid we would reinforce the idea that it is too scary or bad for them to handle."

Rebecka Peebles, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, personal communication, 2019

And then it helps focus the parents too, and we owe it to them as they are doing all the hard work of renourishing:

"We also have so many parents who really think their kid maybe has only 10-20 lbs to gain but actually they have 30-50, and it dramatically alters their concept of the work ahead to get an accurate number."

Rebecka Peebles, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, personal communication, 2019

And it may help parents and clinicians be on the same page:

"Some parents set lower thresholds for weight targets than clinicians believe are healthy. They may do this because they believe their child is constitutionally thin, to make it easier to re-feed, or because of their own weight concerns."

James Lock, co-author of the FBT treatment manual, personal communication

James Lock added that "Of course this is not most parents, but it is an ongoing clinical issue I hear about frequently." On parents' forums I mostly read from parents who are very upset that their child is now 'stuck' at a low number, often announced by one clinician without consulting parents or the rest of the team.

A weight target will need to be adjusted… or let go of

Even with what looks like a well-individualised weight target, nobody should get attached to a number. As your child's weight goes up, there will be more clarity on what they need for a healthy physical state.

"In adolescents, target weight will be adjusted upward to correspond to increases in the patient’s height, and it can be helpful to discuss this with them from the initiation of treatment. During a period of growth, the target weight should be reassessed every 3–6 months.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline 2023 page 33

And then, you'll also be considering their mental state. Since weight recovery is necessary but not sufficient, it's normal for your child to continue having fear foods, eating disorder behaviours and poor body image. You need a good professional to look at the whole picture with you and your child. As discussed earlier, your child might need more weight, more work, or more time.

In my opinion there is a tendency in the treatment world to undervalue the 'more work, more time' bit. Exposure work (Chapter 9 of my book) is overlooked or done haphazardly. Youngsters are made to take responsibility for themselves before there's evidence they're ready (Chapter 10 of my book). Psychological work might be cursory, even with trauma, OCD or autism in the picture.

That can lead to weight gain being the only tool in the toolbox, and I am worried that this short-changes a person in need. So keep seeking good individualised advice.

Quotes from professionals [Click]

Dr Rebecka Peebles points out that at first, physiology is normalised, then more weight is needed to restore hormonal function (e.g. periods return), and then in her experience (and experiences gathered from parents) another 6 to 10 pounds are needed before cognitions (the mental side, the beliefs, the behaviours) return to the person's old normal.

"[The return of periods] is a good marker of pubertal recovery BUT it's not a marker of cognitive recovery."

Rebecka Peebles, FEAST of Knowledge 2024 conference

You're looking for mental recovery, not just physical:

"Before you consider someone recovered, you're not just saying, 'Oh, have they got to the original target weight that I set 6 months ago', but 'Are they really fully physically, pubertally, and cognitively recovered? And if they are, OK, you're in the goal weight range. And if they're not, you might need more weight."

Rebecka Peebles, FEAST of Knowledge conference 2024

"You'll have a goal weight range and we need to aim for the upper end of that range, and if they're not doing well we need to keep going."

"A range of 1-2 kgs on either side of the "target" allows for professional and parental judgment to contribute on whether weight gain is sufficient for health and growth, and based on the changes in THINKING and BEHAVIOR, which are really what need to change to recover from AN even if weight-restored by any definition."

James Lock, co-author of the FBT treatment manual, personal communication

Note that if you mention "1-2 kgs on either side" to your child, it may be very hard to keep raising weight if, as often happens, it turns out they need a lot more. I recommend you set higher expectations, or take the focus off numbers:

"The focus should be not on weight per se but health. This would include absence of signs of malnutrition (such as amenorrhoea, pubertal delay, feeling cold, bradycardia etc.) as well as presence of indicators of healthy functioning (e.g. expected growth velocity for age/stage of puberty, resumption of periods etc.). There will be also psychological indicators such improvements in mood, reduction in ED cognitions etc., etc. In this broader context weight is also relevant as long as we recognize the limitations of the information it provides."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley's Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication

Clinicians use more or less sophisticated tests for physical health. Note that the return of several regular periods is a common indicator (necessary, but not sufficient) for girls. Here's from one of several blogs on the subject by Julie O'Toole:

"At Kartini clinic, we try to focus on 'state', not 'weight'. That is, the state of good health as opposed to a given weight. As measures of this state of health, we use our metabolic labs, including measurements of thyroid health, sex hormones, leptin, glucose, insulin, cortisol and others. We also look at the return of menstrual cycles (related to those same labs), return of energy and normal socialization.

Julie O'Toole, Chief Medical Officer of Kartini Clinic

What we don’t look at is BMI."

About the saying, 'State, not weight'

You may have heard people in the field saying it's got to be about 'State, not Weight'. What does this mean? How can this mantra help or confuse? [Click]

The expression 'State, not weight' probably grew as a protest to the shocking practice of discharging patients as soon as they'd reached a set BMI. Irrespective of weight, when beliefs and behaviours continued to be eating-disordered, we want treatment to continue to restore the person's mental state.

'State, not weight' can also mean that we're not going to obsess over predicting a weight number. When your child keeps asking about a weight target, when they ask 'How many more kilos before I'm allowed to eat and live as I choose', we remember that we're aiming for complete recovery, physical and mental. That's what will govern our decisions around weight and the other tasks of treatment.

It might be better to say we're aiming for wellbeing in 'State and Weight'. We very much care about a person's mental and physical weight, and we recognise that weight is a necessary part of it.

Fitness-lovers who are all muscle and no body fat

In the fitness world, the aim may be to 'improve' body composition, meaning an increase in muscle and a decrease in body fat. A normal or high weight may hide a huge health issue due to insufficient body fat. This is because fat is necessary to many biological processes. Body fat does so much for us, we should think of it as an organ.

Learn more [Click]

A deficiency in fat has long been recognised as 'Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S), previously named the 'female athlete triad'. In female athletes, one sign is absence of menstruation. Body-builders know how terrible they feel mentally and physically as they work on cutting body fat ahead of a competition. With males, an over-emphasis on lean muscularity should raise alarm bells just as much as weight loss or emaciation.

Clearly, the emphasis must go to gaining body fat and halting the muscle-building efforts. This is difficult when exercise is compulsive — a common issue with eating disorders.

* From me: Exercise compulsion with an eating disorder – what can we learn from others? *

* One minute YouTube from Dr Jennifer Gaudiani: Body fat *

* 'Should you be concerned about your son?' by Scott Griffiths *

Larger-bodied people (and fat stigma)

Weight loss in youngsters is automatically a red flag. Combined with eating disorder symptoms, it's a no-brainer that weight must go back up. This applies to any kid, and any eating disorder — not just anorexia.

And it should apply to a kid of any weight — not just those who have become emaciated.

Kids who lost weight but still have a 'normal' BMI (because they started off at a high weight) — these kids are in danger. (As explained in my post on weight suppression and in my post on 'atypical' anorexia). In the wrong hands, they get praised for now being at a 'healthy' weight, and are encouraged to stay that way. It's awful, and it's one of so many reasons why eating disorders need specialist treatment.

"In individuals who lived in higher weight bodies before the onset of their ED, such as those with atypical anorexia, refeeding and weight restoration should proceed with premorbid usual weight taken into account in determining weight restoration goals."

AED Guidebook for Nutrition Treatment of Eating Disorders (2020)

More [Click]

I feel the AED guide (quoted above) is being cautiously vague with the phrase "taken into account". Some therapists and parents are ambivalent about bringing youngsters back up to the higher end of the weight range.

We should reflect on whether a high weight suited our child: were they healthy, did they feel well within themselves, were their eating behaviours well balanced, and so on. When we reflect on their psychological wellbeing, can we disentangle the effects of any body-shaming from peers, in our harsh, fat-phobic society? How can we apply the limited evidence available to get to the weight necessary to beat the greatest health risk to health of all: the eating disorder?

Here are the views of some experts:

Julie O'Toole, who covers the topic in 'Determining ideal body weight' and in 'Coming to terms with my daughter's genetically programmed body size'.

There's a good illustration from Rebecka Peebles's conference talk (FEAST of Knowledge 2024, 26mn in): a girl who hovered around the 90th percentile for weight in her childhood, then went much higher age 10 to 13 when she got her first period. Then anorexia took hold and she shot down to the 50th percentile. Because this is a median BMI, it took a while for people to acknowledge how sick she was at that weight, to begin treatment and insist on weight gain. She got her periods back around the 75th. Cognitive recovery took longer and happened when she settled around the 90th percentile (the talk focuses on weight and we don't know what other treatment work was done).

More on patients with a higher-weight history from Dr Peebles, 47 mn into her podcast with Laura Collins Lyster-Mensh: Episode 21 'State Not Weight'. She also gives a super-informative webinar on YouTube.

"We often encounter patients and families who say “but they looked better when they were a few pounds less” and want to use the eating disorder as an opportunity to keep a person’s weight suppressed. We believe that using an eating disorder as an opportunity to avoid returning to a previous higher weight could hinder the individual from reaching full recovery"

Lauren Muhlheim, 'How we set recovery weights'

It's important that all parties can have respectful conversations to work out the best path for an individual. I have heard of parents being accused of being fatphobic for asking questions. The truth is we all want to work out what's best for this person. The most detrimental factor in their life is the eating disorder. And it's also valid for parents to seek to understand the whole risk assessment picture. To help you with these questions I recommend you head over to this excellent video from therapists Kiera Buchanan and Audrey Raffelt, 'Atypical anorexia or weight stigmatised anorexia?', relating to their ICED 2022 presentation. The whole lecture is brilliant, but for questions like, 'Won't it be unhealthy to bring weight all the way back up, and in any case my child won't cope', jump to 30 mn in.

I say a lot more on these pages:

Youngsters who were 'always' at the low weight end

Has your child been very light, very slight, since they were a toddler? [Click]

Perhaps they've needed to be on a higher percentile for a long time. We know for instance that when kids drop off their weight trajectory at an early age, they are more likely to be diagnosed with anorexia in their teens (see the paper here and a layman's summary here).

Why did they drop? Maybe it was 'normal' for them, but could they possibly have started under-eating because of anxiety — for instance as they started nursery school? Or because there were too many foods that they felt wrong, as can happen with ARFID?

"Anxious kids may manage primary school tummy aches with restricted eating during the school day. Even 3-year-olds learn that thinner is better. I have had multiple teen girls disclose restriction on and off since kindergarten before they fell off the cliff.

JD Ouelette, parent expert-by-experience, personal communication, 2023

Here's an example from Dr Peebles, talking about a child born at a normal weight who dropped off and then stayed on the 3rd percentile BMI for their age:

"and if there appears to be no reason for them to always have been so small, we're often pushing for the 15th to 25th percentile BMI-for-age so that we can give them a robust chance at not having difficulty with eating.

Rebecka Peebles, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, 46mn into podcast 'State not Weight'

This is yet another example of how we must be cautious with percentile growth charts — we should not assume that a child must track along a centile curve.

The abandoned underweight

When you think of the dismal recovery rate quoted for various eating disorders, bear in mind that traditionally, patients were often allowed to stay underweight. Their weight target was based on a low BMI figure, or a low weight-for-height percentage. This still goes on in places. Indeed, let's remember that '100 percent weight-for-height' is a middle-size-fits-all figure, and so it's bound to underestimate the needs of half of our children.

Let's also remember those with 'atypical' anorexia nervosa, who are not told to regain lost weight because their BMI is now 'normal'. These are the abandoned underweight too.

Click for more

With adults who voluntarily attend treatment, there can be a fear that the patient will walk away, or will step up their restricting, if required to gain more weight. The clinician may also believe that a low weight is good enough for recovery. As a result people can live with not-too-bad a physical state — but their weight is too low, and their anxious control over food too high, for the eating disorder to ever be beaten. With anorexia, these people get the tragic label of 'functioning anorexic'. Those who do a bit better may be considered in 'quasi-recovery'.

Our sons and daughters need empathy and food, not a lower weight target.

Should your child be told about a target weight?

Some clinicians explain to the child the weight they're aiming at, and some don't.

"Typically, the target weight will be discussed explicitly with the patient, but this can require considerable sensitivity. On occasion it may be judicious to delay this discussion until the patient is less fearful of their ultimate weight."

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline 2023 page 33

What's for sure is that the child needs to know that the whole team is focused on the need for weight gain. That can't be a secret. More here. [Click]

"As long as this message comes across as caring and an expression of a wish to promote long term well being (rather than being controlling and unwilling to listen) most young people with anorexia go along with the need to gain weight, albeit grudgingly and with perhaps (unpredictable) meltdowns. We have argued that, as long as the message about the need for weight gain is experienced as an expression of care, the young person, in spite of being scared, finds it at some level reassuring."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley's Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication. 2019

Be really careful with any numbers you say aloud. Our children can fixate on a target as their maximum. Giving a range can be just as problematic while eating disorder thinking is strong: our children hear the top number as a limit.

"As a HAES provider, I have moved toward setting a minimum weight rather than a weight range for my patients […] A weight range implies that there’s a weight above which they’ve gone 'too high.’"

Dr Jennifer Gaudiani, internist and expert on the medical complications of eating disorders, in 'Weight goals in anorexia nervosa treatment' (HAES is 'Health At Every Size')

I believe that the way we talk about optimum weight or weight range evolves as our children recover. While they're deep in the eating disorder, they anxiously distort our words and it makes everything harder. And our focus is on lots of food for rapid weight gain. After they're weight-recovered, surely the conversations need to change, so that they can learn or re-learn how balance works in normal life. More on this further down.

As we saw, for some therapists, talking about a weight gain goal is part of the therapy. Parents, you can ask for an appointment without your child, in order to learn more:

"We walk the parents through a step by step explanation, with their kids' historical curves. We then let them know it is our recommendation to only tell their kid the highest number in the range, as the kid cannot ‘unhear‘ the lowest number."

Rebecka Peebles, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, personal communication, 2019

Parents and youngsters need different conversations:

"We then tell the kid the highest number – with phrasing like, ‘A goal weight is just our best estimate of where your body and brain will work best. It's also going to move up as you get older and/or taller, so the goal is a moving target and will go up. It’s based on where you were healthy long before this illness. Because kids grow all the time, any number we say is going to probably be the highest you’ve heard and it will probably feel upsetting, but it’s important we go over it so that you’ve heard it and the numbers seem less scary over time. Keep in mind that we are flexible on your goal weight and if your brain and your body are completely better earlier than we think, that’s fine. Likewise if you’re not totally better or not thinking clearly at the number we say now you may need more. We are fine as long as you are really truly fine and your eating disorder is gone.'

Then we tell the kid the highest number in the range. Watch the meltdown. And then keep going."

Rebecka Peebles, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, personal communication, 2019

Often, the meltdowns happen not in the therapist's office, but in the car on the way home. The parents need all their parently skills to weather the storm (see chapter 14 of my book) and make sure the next meal is eaten (in particular chapters 6, 7 and 8 — there's also loads in my Bitesize audio collection). parents can do this a lot more confidently when there's teamwork with clinicians.

Note that Rebecka Peebles, whom I quoted above, is not dogmatic about telling all kids their target weight: "If I see a 7 year old who has no concept of weight at all, then we won’t. If parents refuse permission we won’t. But it’s really hard to do good work without being transparent."

And at any age, it's "not a one-size-fits-all" and "there's a time and a place":

"If parents indicate their child cannot tolerate it, then I'm willing to wait. […] It's a question of when is best. I want to talk with the kids and the parents and see what makes the most sense. If patients are saying, 'I have to know, I have to know!' but it's clear, they're very honest, that if they hear a number that they can't handle then they're going to stop eating, then that's probably not a time to talk to them about it."

Rebecka Peebles, FEAST of knowledge 2024 conference

When a child is declared 'weight-recovered', with no consultation with parents, without any careful assessment of their physical and mental state, usually using a middle-size-fits-all figure, we parents have to jump into damage limitation mode.

"When my daughter, still quite ill, came home from an individual therapy session saying, 'She told me I'm at 100 percent and that's my perfect weight', I replied, 'I'm sorry you heard that. Nothing is changing before all the adults review this together."

Eventually, if a therapist will not engage in discussion and insists that the weight given by their calculator is what your child needs, you might have to tell your child, as I once did to mine, 'I'm sorry darling, I've studied this and I know better'.

Should your child see their weight? Blind versus open weighing

The question of blind weighing versus open weighing is hotly debated. I'll keep it brief here. [Click]

Other tasks of recovery: weight recovery doesn't fix everything

It's normal that your child should still have an eating disorder when they've reached weight recovery. Remember that weight recovery is necessary but not sufficient. Put it this way: the real work of eating disorder recovery starts after weight restoration.

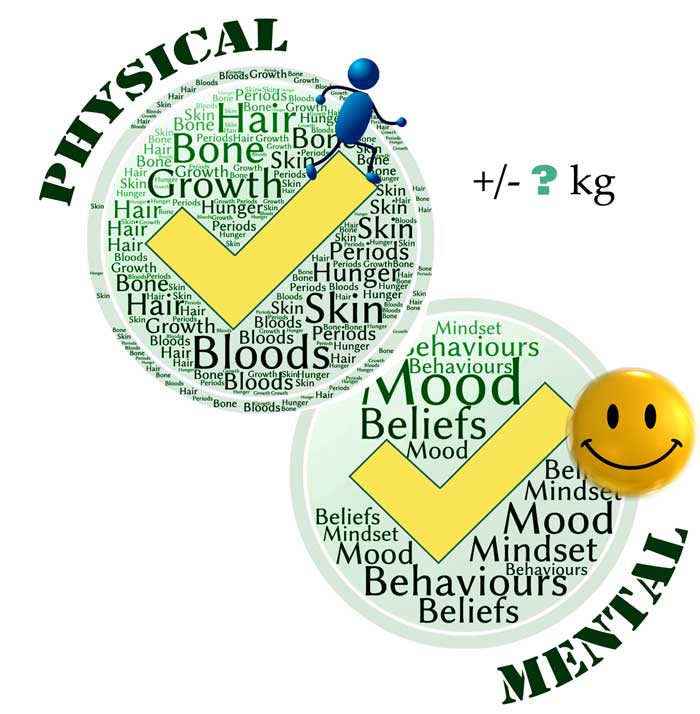

Take heart — there are methods to shift the mental and behavioural 'stuckness'. Look at this rough guide below. Notice how weight recovery is only part of the picture.

Indeed, weight restoration is just one element of eating disorder recovery. It's necessary, but not sufficient. Here are the four elements, as I see them:

- Biological: weight restoration, good nutrition, rest etc. Too many people think that's all FBT is about.

- Behavioural: phasing out eating-disorder behaviours, replacing them with 'normal' ones, and through exposure and repetition and brain rewiring, fading out fears and changing beliefs.

- Part of bringing back normality is the often-mishandled 'Phase 2' work of FBT, where we guide our children back to age-appropriate independence.

- Psychological: addressing any prior anxieties, depression, trauma, bringing back self-esteem/self-compassion, good emotional management and returning to a full, enjoyable life. Part of this is 'Phase 3' of FBT.

In other words, when the body is fine and the mind isn't even close, it may be a sign that:

- more weight is required because the method used to set the weight target was very inaccurate — see my other post in which I warn of how very wrong some targets can be

- or that more weight is needed because the body needs to drive a growth spurt

- or more weight, or more body fat, is needed, because there are biological processes that need it (a well-known example is regaining healthy estrogen level to get periods back)

- there's a need for exposure work to help change habits, beliefs and extinguish fears

- or that the person needs more support and monitoring so that they keep practicing helpful behaviours

- or for psychological work (anxiety, depression, OCD, traumas etc)

- or that time is needed for all biological and mental systems to return to balance

- or that time is needed for life to bring maturity and richer interests

Does my child need more weight, more recovery work, or more time?

From the above, you'll appreciate that there is always a level of uncertainty on whether a person needs more weight, or more work, or more time to reach complete recovery.

Click for more on this

Above is an example of one persons' eating disorder difficulties, and how weight recovery wasn't the whole answer for all of them. So, it did fix the OCD handwashing issue, but exposure work was needed in addition to weight recovery to expand the person's range of foods and exercise compulsion. Regarding body image, time and a good life were also part of the solution. And throughout, progress would have been lost if this person had been given too many freedoms too soon (Phase 2 of FBT).

"The problem is, there is a cohort of people out there who believe that weight restoration will solve all of the problems associated with this terrible brain disorder. It does not always do so — in fact, in my experience, although weight gain is the foundation of the house we are building, it is not the house."

Julie O'Toole, Chief Medical Officer of Kartini Clinic Kartini Clinic, in The treatment of pediatric anorexia nervosa

An analogy: back to my azalea

I've already proposed that the amount of watering that suits my azalea is a bit like a person's optimal weight range. Water is necessary, but not sufficient. When my azalea is dropping flowers, I first wonder if it needs more water. I also consider that more water might not be the answer. Maybe it's outgrowing its pot. Maybe it's getting too much direct midday sun. And so on. When it comes to people, aren't our needs vastly more complex?

Discharged upon 'weight recovery'?

Sadly, children are often discharged from treatment as soon as (or even before) they've reached a target weight. And yet there's so much work still to do, and you're dealing with such a new situation!

Once your child has reached some rather fuzzily defined level of weight restoration, my guess is that the mechanisms of appetite and the body's needs enter a new phase. And there's a new psychological landscape. Your child deserves expert help with how to think about what is 'normal'; how to live in balance.

The 'food is medicine' mantra was crucial early on in treatment. Upon weight recovery — just when people tend to get discharged — the treatment really begins. A different kind of medicine is needed, and it's got to be individualised.

When parents point out the behaviours and thoughts that still afflict their child, some get told, 'There's nothing more we can do', or ' 'It's time that Annie takes responsibility for her recovery.' I've even heard, 'Consider yourself lucky, because we normally discharge much sooner'.

If you're in this situation, remember that there's a lot more to treatment than weight gain, and if you can't get a more experienced clinician, there's guidance to do it yourself (more in Chapters 9 and 10 of my book, and my Bitesize audios).

Body image is particularly slow to return to normal

It's particularly common for body image issues to require more time:

"There is general agreement among clinicians that distorted attitudes about weight and body shape are the least likely to improve with weight restoration and typically lag changes in weight and eating behavior"

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline 2023

Incremental steps in search of optimal weight range

With all the uncertainties I describe on this page, how might an expert proceed? Well they might take a patient to their best recovery weight estimate — an individualized estimate, of course, not one plucked out of a calculator. Then they might stabilise the person there, and step up the work on other tasks of recovery mentioned above. Then if the person continues to be stuck, they may proceed in increments. They experiment with a little more weight, while renewing their attention to exposure work, psychological work, and the person's life. Experiment, and proceed in increments.

Actually, I don't often hear of this approach being used (I head it from Ivan Eisler of Maudsley, UK), but it makes sense to me. Isn't that how long-term medication is dosed? Women on HRT… People on thyroxine…

'You can't raise my goal weight!'

Some parents and clinicians are really nervous about bringing weight up, when there'd been a prior belief their child was weight restored. They're scared it will drive their child to rebel and restrict. But what's new? They've already proved they can support their child even through these 'I feel fat' crises. Perhaps they share their child's resistance to a less thin body, because our society privileges those who are thin. So ask yourself: if there was a chance of saving a life using a medicine that caused weight-gain, would you have any hesitation? We must all do a little self-awareness and check if we are suffering from a whiff of fat-bias. In this society, it would be strange if we were immune.

"Even treatment providers may be susceptible to weight stigma encouraged by society's war on obesity. Consequently they may err on the side of under-restoring a teen in recovery."

Lauren Muhlheim in 'When your teen has an eating disorder'

"Unfortunately, many medical professionals, nutritionists, life coaches, and therapists have not yet done vital work on understanding their internalized thin biases, and they end up subscribing to and recommending practices that are grounded in diet culture. This is very harmful for everyone, but particularly so for those recovering from eating disorders."

Dr Jennifer Gaudiani, internist and expert on the medical complications of eating disorders, in 'Weight goals in anorexia nervosa treatment'

Beyond a knife-edge: build a buffer

Many individuals have seen very clearly that if weight drops below a tipping point, eating disorder symptoms return in all their former glory. There's a minimum weight they need for mental wellbeing, and it's higher than the minimum needed for physical health.

"As soon as she would hit 1 pound [0.5 kg] under [xxx weight] the 'voices' and behaviours would come back with a vengeance. So now during exams she ups her fat intake a lot. She doesn’t weight herself but she just knows because of the thoughts."

The mother of a 20-year old

To avoid living on a knife edge, wise clinicians will help you factor in a buffer.

"My relapse taught me that for my own body, the difference between health and illness can be quite a narrow margin, just a handful of pounds. The simplest solution? Don’t live so close to the boundary."

Emily Boring, in an enlightening piece 'When in doubt, aim higher: What I wish I'd known about target weights in recovery' Listen also on this podcast

A person may fight the notion of even a small buffer because they've focused on one magic number and fear anything above it. As a parent, you can continue to be compassionately firm about the need to continue the work. This means you should resist giving too many freedoms (Phase 2 of FBT) and be cautious if your child is discharged from treatment before this work is done.

A recovered person's relationship with weight

All that hard work to beat an eating disorder! We owe it to our children to help them develop a happy, relaxed relationship with food, exercise and weight. Think about the weight-gaining phase of treatment: it's like tough medicine, and it's time-limited. It's not 'normal' life. We serve up big amounts, impose rest, and focus on rapid weight gain. Once our children are considered weight-recovered, surely they need guidance to learn or re-learn stability.

Surely that's not going to happen overnight. It's likely to need a different focus at different stages, for different people. Some might need a period of rule-based eating. Some might need more exposure work: to food, or to a higher weight than their magic number (more on this below). For some, later, there may be experiments with aspects of intuitive eating. And each person will find what brings them a sense of freedom and stability. All this surely deserves professional guidance.

One of the tasks is to loosen the attachment to a magic weight-recovered number. Often, our children make it their psychological maximum. They're happy to regain weight if it happens to drop a little, but nothing beyond! They control their eating and exercise to avoid a feared zone above the magic number. This is, of course, eating-disordered. And it also means they can fall off their growth curve, further strengthening the illness. So treatment has to evolve to address this thinking.

Our children probably fear that without tight control, they will always eat too much. They may remember how they dreamed of feasts while they were starving.

Many of their role models could be dysfunctional — we're in a society where we're told to diet, calorie-count and reshape our bodies.

We parents can still be attached to the 'more food, more weight' message that was such effective medicine in a first phase of treatment. And at first, it's indeed a welcome antidote to the (usually awful) 'health promotion' messages that often triggered our children's eating disorder.

So, by the time our children are weight restored, we can view a word like 'moderation' with suspicion. Is this kind of moderation, for this person, at this stage of their recovery, still a cover for restriction? Is it based on fear and self-judgement? Some people might hold the view that any kind of moderation is an eating-disordered concept. Personally, I note that moderation is beneficial in most aspects of life. Many biological processes have a happy sweet spot — not too much, and not too little. The fact we're even discussing this indicates that in the later stages of treatment, individuals deserve help with these questions.

I propose that parents and clinicians have a role in supporting the new experience of living in a happy zone. That means our children should not be discharged as soon as they're weight-recovered — or if they are, they know that the work must continue within the family.

It also means that for a while, there are some freedoms (Phase 2 of FBT) that our children can't yet handle. They need our 'holding' and our guidance while they experience how food, exercise and weight are all going to work out in the long term.

Principles of exposure therapy come in here: to experience that optimum weight for wellbeing is not one number, but a relaxed, flexible range. To discover how normal it is for weight to vary by plus-or-minus 1.5 kg or so in any given month or day. To learn how one's appetite functions, how the body wants to rest or move, and how to function in a society that judges weight and appearance.

'Overshoot' and hunger

You might have heard of 'overshoot' and of 'extreme hunger'. Parents ask me about it, and here's the best guidance I can give you at present.

Click for more

Among some adults in recovery from an eating disorder — especially anorexia — there's a theory that to recover, a person's weight needs to overshoot for a while.

They report that overshoot was necessary to normalise their own beliefs and behaviours and to improve their mood. Extreme hunger drove their weight significantly above the target they were given. The important point is that as this happened, the eating disorder disappeared permanently.

Some parents have shared similar experiences about their child.

In most — but not all — accounts, the person experienced some distress or resignation during the period of overshoot. They didn't enjoy the changes in their body and had to trust it wouldn't go on for ever. They chose to 'honor their hunger' without self-judgement. They resisted the urge to compensate with restriction and over-exercise. This helped them steer clear of harmful yoyo dieting ('weight cycling'). Some were motivated by the assurance that this phase is necessary, and it will pass. These quotes from a couple of parents show the pay-offs along the way:

"Her voices and behaviors stopped. It was absolutely the magic wand."

“As her weight increased, her mental and emotional health grew stronger. “

Advocates of overshoot report that appetite settled, and weight gradually and naturally dipped: the eating disorder had disappeared during the weight gain phase, and the subsequent dip happened without any deliberate restriction. Weight settled smoothly around pre-restriction levels.

For reputable authors/bloggers on this topic for adults, see Emily Troscianko, Tabitha Farrar, Amazonia-Love, Helly Barnes. For youngsters, this is the happy experience of a couple of parents who got in touch with me:

"When she was losing, at first I thought it was due to relapse, but I see her eat 5 of her 6 meals, she is eating the same way, snacks freely, no exercising, not vomiting. There are none of the telltale signs I've learned to identify: she's not striving for perfect grades, she has friends over all the time, her room is messy, she can wear non-baggy clothes, there's no drama or odd behaviors around meals, and the non-stop negative self-talk has gone.

“Her hunger cues normalised and she began to lose weight gradually. Those around her noticed it before she did. Weight loss occurred over the course of a year and then stabilized. This was a scary time as we tried to figure out if this could be a relapse, but no clear signs of relapse emerged. She ate freely and exercised very minimally.

Her mental and emotional health remain strong and she is excelling in school, work, and relationships. She honestly is functioning at her best, including pre-eating disorder.”

Because full recovery has been the wonderful outcome for some, there is talk that 'overshoot' is necessary for everybody, and that 'extreme hunger' is a reliable sign of a biological need for more weight. Some people are certain that it's the process of overshoot that brought them full recovery — that without it they'd still be ill.

They entreat you to 'honor your hunger'. To consider your big meals to be 'catchup eating', not an episode of binge eating. In their view, 'moderation' in eating is the same as restricting, i.e. engaging in eating disorder behaviour (I say a bit about moderation earlier). There can be a view that if you're thinking of having another serving of pizza, it's a biological sign your body needs more weight and is necessary for full eating disorder recovery.

Perhaps your child is enjoying their big meals and doesn't care about their increasing weight. They're feeling great! If so, you don't need to read any more.

But some are distressed, and for those, I would like an expert to provide individual guidance. I am worried about blanket rules for all, given that appetite, weight, metabolism, hormonal function, psychology, are hugely individual. And given that there is no research to compare overshoot with no-overshoot.

Is insatiable hunger a biological signal that more weight is needed? While that might be true in some situations, I'd question whether that's the full explanation. Hop over to a flowchart on this YouTube by Cara Bohon to eyeball the numerous, interrelated factors that shape our eating behaviour.

An analogy might be this: if you were sleep deprived, you'd definitely want some catchup. But if after that you continued to be constantly tired, wanting to sleep all the time, and feeling terrible about it, you'd deserve to have an expert checking out all the possible reasons for your tiredness.

In terms of research, people usually point to the Minnesota starvation study, where young men experienced 'extreme hunger' and 'overshoot' once the severe eating restrictions were lifted. Scientists have tried to analyse the drivers. It's no doubt one piece of a puzzle. But I am worried about generalising too much from the specific regime these men went through.

In case you're hearing that overshoot is necessary for all, please know that plenty of people recovered without overshoot. Just look at published research on various treatments. And plenty did not go through extreme hunger.

Remember also that weight cannot be the only tool in the toolbox. Check that you're attending to all the tasks of eating disorder recovery. Notice that those who've worked hard at tolerating overshoot have put themselves through those tasks — consciously or not.

Also, ask yourself, 'Overshoot compared to what?' So many people have been given a stupidly low weight target, and we're not yet seeing the end of that, sadly.

If your child is experiencing extreme hunger, or seems to have moved into binge eating disorder, or if their weight is ever-rising for no clear reason, I think you and your child deserve expert help, not blanket advice off the internet.

(If you have been diagnosed with an eating disorder and you are using this section to justify restricting, while dismissing all my other sections about the need for full weight recovery, then you very much deserve expert help.)

Look for a registered dietitian who specialises in eating disorders, so that they can be really cautious with someone who's only recently emerging from anorexia. Personally I'd want one who also helps people with binge eating disorder, as some of their expertise may come in even if you decide that meals driven by extreme hunger are not binge eating episodes. Look for someone who uses words like 'weight neutral' or 'weight inclusive'. Interview them. Avoid anyone who promises weight loss, or who states that it's unheathy to be above a certain weight. You probably want someone who advocates for the 'Health At Every Size (HAES)' ethos, though it's worth asking them what it means to them. Check if they have a blanket approach, like 'Honor your hunger', irrespective of any other factors. Will they accuse you of fat phobia if you try to educate yourself on these matters? If they subscribe to 'Intuitive Eating,' will they first investigate if your child has reliable hunger and fullness cues, with all hormonal processes back on track? Will they spend time getting to know your child as an individual — their wishes, their distress, their emotions, their attitudes to food and body, their habits, their beliefs, their biology?

I am painfully aware that you may not have access to a great professional, so all I can advise is proceed experimentally, as proposed earlier.

See Chapter 10 in my book for more help on food and weight after weight recovery.

What to do with all the uncertainty? Experiment, proceed in increments, and review

I'll end with a reminder that weight restoration on its own doesn't fix an eating disorder. But weight restoration is essential. What weight that means for your child: that is full of uncertainty.

From every expert I've learned from, my (current) conclusion is that we accept that we cannot know a recovery weight until we're roughly there, after which we proceed in increments.

And meanwhile, we remember that weight isn't the only factor in recovery from an eating disorder. We do exposure work to normalise behaviours and beliefs, we are careful not to give freedoms that our child cannot yet handle (Phase 2), while coaching them the best we can to handle them soon. We provide psychological help where appropriate, try and make life rich and interesting, and also allow time to provide some of the repair that the body and mind might need.

As with everything which presents us with uncertainty, we can experiment with all this, taking it in incremental steps, and review.

"An important part of the later stages of the process of recovery is to accept that one needs to learn to tolerate uncertainty. This is a difficult piece not just for the recovering young person but also for the parent — and in different ways for the clinician. It would be wonderful to be able to have something specific and measurable that would tell us when it is safe to back off and let the young person get on with their life – if only."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley's Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication, 2019

More help from me on the topic of weight

* Experts say, "Recovery weight must be individualized" *

Quotes from eating disorder experts on weight targets: researchers, professional bodies, and the clinicians who may well have trained your clinicians!

* Is your child's target weight a gift to the eating disorder? *

Comparing two methods therapists use to determine a weight target: growth chart + adjustments, versus the one-size-fits-all BMI approach. The difference can be huge!

* What do BMI and Weight-For-Height mean? *

What BMI and Weight-for-height (WFH) and BMI z-scores mean, and how they cannot be used for advice. Read this if your child’s therapist uses BMI or WFH.

* Weight gain in growth spurts *

To help you let go of weight targets, I remind you that youngsters' growth is unpredictable and can go in spurts.

* Weight centile growth charts: why they can’t predict your child’s recovery weight *

How growth charts cannot predict a healthy weight for your child: I show you how they fail to show normal variations in healthy individuals and remind you that you won't know your child is weight-recovered until they get there.

If your child has failed to gain weight with age, or has lost weight, that's weight suppression. Make sure your clinicians aren't only looking at your child's current weight: here's evidence that the amount and speed of weight loss matter at least as much.

* Atypical anorexia diagnosis? Handle with care! *

What's 'atypical anorexia', the issue with weight being declare 'normal' or high, the risk from malnourishment and the need to regain lost weight.

* More on weight and feeding in Chapter 6 of my book *

From others:

* Poodle Science: a YouTube from Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH): A short fun video that makes the point that one size does not fit all

* The importance of sufficient weight gain is beautifully covered by Dr Peebles talking to Laura Collins Lyster-Mensh in podcast Episode 21 'State Not Weight' *

* Research indicates that going 'slow and low' is not to your advantage. Here are resources about the need for rapid and complete weight recovery [click]

Start with an excellent talk, backed up by data, to help you understand the benefits of rapid, full weight restoration: Alix Timko, in ‘Challenging Parent Perceptions on Weight, Fat, and Food’, youtube.com/watch?v=1Fzjx0VO438 She references studies, including some of these:

A good predictor of success with FBT is adolescents gaining 3 or 4 lbs by week four. Doyle, P., Le Grange, D., Loeb, K., et al, ‘Early response to family-based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa’ in J Eat Disord (2010) 43: 659-662. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20764

A later study recommended a gain of at least 3.20 kg in the first 3 weeks: Le Grange, D., Accurso, E. C., Lock, J., Agras, S. and Bryson, S. W., ‘Early weight gain predicts outcome in two treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa’ in International Journal of Eating Disorders (2014), 47(2), 124–129 https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22221

Rapid refeeding of adolescents, 2400-3000kcal/day, mean gain of 5kg at 2.5 weeks: Madden, S., Miskovic-Wheatley, J., Clarke, S. et al. Outcomes of a rapid refeeding protocol in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa. J Eat Disord (2015), 3(8) https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-015-0047-1

An inpatient study showed that a gain of at least 0.8 kg per week predicted a better year-1 outcome: Lund, B. C., Hernandez, E.R., Yates, W.R., Mitchell, J.R., McKee, P. A. and Johnson C. L., ‘Rate of inpatient weight restoration predicts outcome in anorexia nervosa’ in Int. J. Eat. Disord (2009), 42(4) https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20634

Another study found that a shorter duration of illness prior to treatment beginning was a predictor of successful weight gain: Agras, S. W., Lock, J., Brandt, H., Bryson, S. W., Dodge, E., Halmi, K.A., Jo, B., Johnson, C., Kaye, W., Wilfley, D., Woodside, B., ‘Comparison of 2 Family Therapies for Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa. A Randomized Parallel Trial.’ In JAMA Psychiatry (2014), 71(11) https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1025 Contradicting other findindings, this study showed there was no difference at end of treatment, and a year on, between those who had gained weight fast with FBT, or more slowly with systemic family therapy. There were fewer hospitalisations with the FBT patients, though.

Nowadays, inpatient units often raise weight faster than 1 kg a week. This is a welcome turnaround from previous slow gains which kept people in hospital for many months.

There used to be a belief that rapid gains are traumatic, or that ‘the mental has to catch up with the physical’). This has now been overturned, e.g. in Guarda, AS, Cooper, M, Pletch, A, Laddaran, L, Redgrave, GW, Schreyer, CC. Acceptability and tolerability of a meal-based, rapid refeeding, behavioral weight restoration protocol for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord (2020), 53 https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23386 For a summary, see medicalxpress.com/news/2020-12-anorexia-patients-tolerate-rapid-weight.html

Anything by Dr Jennifer Gaudiani on the subject of weight and body fat is fascinating. eatingdisorderrecoverypodcast.podbean.com/e/dr-g-metabolism and her book ‘Sick enough’.