Your cart is currently empty!

Weight-restoration: why and how much weight gain?

So many questions on weight gain and healthy weight!

This is my main page on weight restoration. I’ll explain:

- why restoring a healthy weight is necessary to treat an eating disorder

- how it’s not sufficient — there’s work to do, in addition to weight recovery

- for almost everyone, if you know how much weight was lost, that’s an absolute minimum that needs to be regained.

- weight has to increase with the growth needs of a young person

- what people report about the need for a weight buffer, or for overshoot

- if a goal weight is announced (and I give pros and cons), it can only be a rough estimate

- when predicting goal weight, most clinicians use only a few of the recommended criteria for assessment: I explain the methods most often used and why their predictions can be very wrong

- you can’t pronounce someone is weight-recovered just because they’ve reached a predicted goal weight: if they still have issues with their physical or mental state, there is uncertainty on whether more weight, more work, or more time are needed.

- how you’ll need to experiment with weight and time if your child is ‘stuck’

My overall message will be for you to focus on the work of recovery without seeking precision regarding goal weight: you’ll only know you have weight recovery when you’re seeing your child is well, both in their physical and their mental state.

Why does weight matter?

A healthy weight is necessary for recovery from an eating disorder. Without a healthy weight, the eating disorder will stay. A healthy weight and body composition are necessary for the wellbeing of the body, the brain, and the mind.

"Attainment of appropriate body weight in anorexia nervosa is a critical element of full recovery. A person can be insightful, motivated, successful, and doing better than they were before, but unless they have achieved full weight restoration, they remain at medical and psychological risk and aren’t well. This is pretty well accepted."

Dr Jennifer Gaudiani, internist and expert on the medical complications of eating disorders, in ‘Weight goals in anorexia nervosa treatment‘

"[Insufficiently high] BMI at the end of treatment is a predictor of relapse"

Frostad et al (2022) – from review of almost 1400 anorexia patients

In the Frostad review quoted above, having a BMI at the lower end of the ‘normal’/’healthy’ BMI range was the strongest predictor of relapse. Weight needs to be higher.

A healthy weight is not a designer choice but a biological imperative.

"Weight gain is key in supporting other psychological, physical and quality of life changes that are needed for improvement or recovery"

NICE guideline for eating disorders (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence)

"Like other medical indices (blood pressure, heart rate, etc), weights are medical indices"

NICE guideline for eating disorders (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence)

If your child has been restricting (whether because of anorexia or another eating disorder — or indeed, any illness), their weight is not where nature intended. They must recover lost weight, plus catch up with lost growth, plus keep growing. A child or adolescent’s weight has to go up.

By the way, I mentioned ‘body composition’ because healthy weight gain does not mean just gaining muscle. Body fat isn’t just padding: it has an active role in our body, including the production of essential hormones.

The weight nature seeks

"There is considerable evidence that our weight is genetically influenced. Research suggests that our minimum weight cannot be significantly altered over the long term. This hypothesis is called ‘set-point theory'[….] The aim of any treatment has to be to help [patients] to live and eat more healthily. This means helping them to eat regular healthy meals (which might or might not lead them to put on weight) and, if they do gain some weight, helping them to accept this weight as the one that they are ‘meant to be’ (wherever it may be within the healthy BMI range)"

Glenn Waller et al in the CBT Manual ‘Cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders‘

You can read more on set-point theory here. In general, from what we see of adult dieters, the body seems to push to regain its highest weight. With our children, regaining lost weight is an absolute minimum, and more is needed for growth. Plus, the body may require more for healing.

Consider a healthy or normal weight as one that is conducive to physical and mental health. In adults that have stopped growing it’s also a weight that is effortlessly stable when people eat flexibly to their appetite, without restricting or bingeing.

Regain weight… now!

During the early stages it is generally entirely appropriate to be focused on the need for weight gain.

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley’s Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication

It’s a no-brainer. If your child has been restricting, they need to gain weight. Don’t waste time wondering ‘how much’. Their body is in famine mode. It needs nutrition and weight gain. Start regaining what was lost. If you have no idea how much was lost, a good eating disorder clinician will still prioritise weight gain.

Weight gain is, obviously, needed for physical repair, but is also essential for the mind (see for instance Accurso et al‘s study ‘Is weight gain really a catalyst for broader recovery?’ and Dr Sarah Ravin’s plain English summary of it.)

"It is well established in outpatient and higher levels of care that early and steady weight gain is associated with good prognosis"

AED Guidebook for Nutrition Treatment of Eating Disorders (2020)

So, start refeeding.

This isn’t just for anorexia, and this isn’t just for low-weight individuals. With an eating disorder, including bulimia or binge-eating disorder, there is usually a component of restriction. If someone has lost weight, or failed to grow, they need weight gain. Also, all eating-disorder sufferers need regular renourishment, whatever their weight or body shape.

The only reason not to refeed fast now is if your child is at risk of refeeding syndrome. Check with a professional. (What’s normally meant by ‘fast’ is half a kilo to one kilo a week at home, and usually twice as fast in an inpatient setting — more on this in Chapter 6 of my book.)

If your child used to be labelled as ‘overweight’, or still is, it makes no difference: their health needs to be checked and if they lost weight they now need to increase it.

"I do not know how many times I have been told by a parent that their pediatrician dismissed their concerns about their child’s weight loss as ‘not a problem’ because they were ‘still on the normal BMI chart.’"

Julie O’Toole, Chief Medical Officer of Kartini Clinic in The misuse of BMI in diagnosis of pediatric eating disorders

Some treatment providers like to estimate a goal weight very early on. I’ll discuss pros and cons of you and your child being given any kind of number. What is sure is that a goal weight is no better than a weather forecast, and must not be a criterion for treatment ending. When your child reaches the predicted number, they may be well, or they might need more gain.

Weight restoration: essential but not sufficient for recovery

"Although weight restoration is a goal for FBT, it is not sufficient. If weight restoration was sufficient for treatment of anorexia we would have cured it along ago."

James Lock, co-author of the FBT treatment manual, personal communication

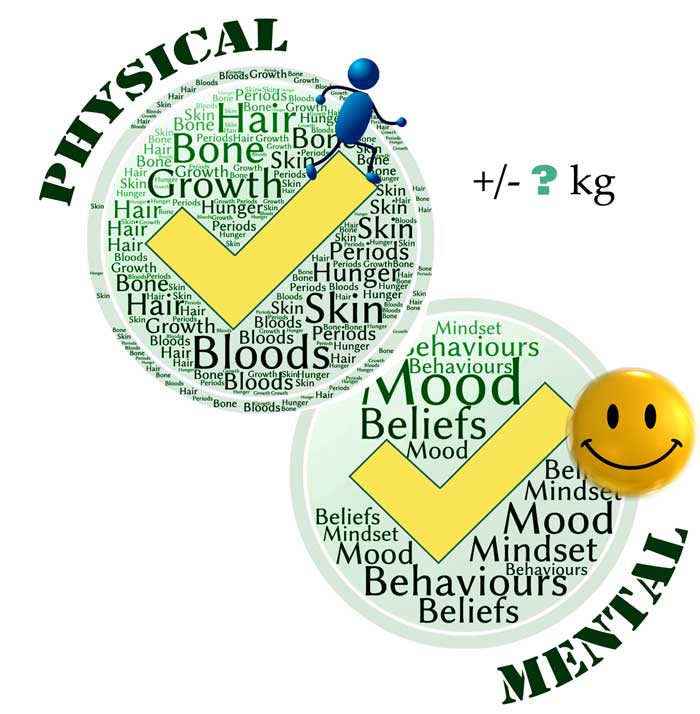

Indeed, there are three main elements to eating disorder recovery, and weight restoration is just one of them. It’s necessary, but not sufficient. Here are the three elements, as I see them:

- Biological: weight restoration, good nutrition, rest etc. Too many people think that’s all FBT is about.

- Behavioural: phasing out eating-disorder behaviours, replacing them with ‘normal’ ones, and through exposure and repetition and brain rewiring, fading out fears and changing beliefs. Part of bringing back normality is the often-mishandled ‘Phase 2‘ work of FBT, where we guide our children back to age-appropriate independence.

- Psychological: addressing any prior anxieties, depression, trauma, bringing back self-esteem/self-compassion, good emotional management and returning to a full, enjoyable life. Part of this is ‘Phase 3’ of FBT.

All three components take work, and most importantly, time is a key ingredient in all this. If your child’s mental state is poor, it could be that one, two or three of those components need more work or more time. This means there is always a level of uncertainty on whether a person needs more weight to reach complete recovery.

"The problem is, there is a cohort of people out there who believe that weight restoration will solve all of the problems associated with this terrible brain disorder. It does not always do so — in fact, in my experience, although weight gain is the foundation of the house we are building, it is not the house."

Julie O’Toole, Chief Medical Officer of Kartini Clinic Kartini Clinic, in The treatment of pediatric anorexia nervosa

When ‘recovery’ weight is too low

There is no such thing as a universal minimum target weight. People vary dramatically in terms of body build, muscle mass, bone structure, body shape, and natural weight […]Many patients are left to struggle with ongoing depression, fatigue, anxiety, and preoccupation with food and weight because they haven’t reached their optimal body weight.

Dr Sarah Ravin, in 10 Common Mistakes in Eating Disorder Treatment

Weight is a bit like shoe size: there’s a size that fits your child, and it’s probably different from their friends’ shoe size. It could be smaller than average, or larger. Sure, there’s a little more flexibility with weight than with shoe size, but every respected expert I can think of will tell you one can’t beat an eating disorder with ‘too small’.

And just as we don’t expect our shoe size to go down, we don’t expect people with an eating disorder to function well when weight-suppressed.

"There are certainly people who get stuck in the recovery process at a weight that is too low for them."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley’s Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication

Therapist Lauren Muhlheim asks ‘Are we setting recovery weights too low?’ here (and pretty much answers, ‘yes’). Likewise:

"It is clear that under-nutrition cannot be good—yet as practitioners, many of us contribute unintentionally to this mistake every day. How so? By allowing patients to remain slightly below a weight that represents real physiologic restoration for fear that they will not be able to tolerate the anxiety of returning to a “non-skinny” weight/BMI.

Julie O’Toole, Chief Medical Officer of Kartini Clinic, in ‘The dangers of staying slightly below weight‘

With a family-based model, we don’t need buy-in from our children. We support them to eat, meal after meal, in spite of their fear. With time and weight gain, their resistance to weight gain usually reduces as they experience that they look and feel fine.

Note that it’s normal for anxiety over body shape to spike every now and again, but it abates as people are supported to push through. In particular, there may be anxiety a few kilos before weight-restoration (see Dr Anna Vinter’s article about this phenomenon, which some refer to as the ‘extinction burst’) where it’s particularly important to keep going.

"The anxiety over being fat is more likely to significantly improve with recovery, more regular eating patterns, and — ironically — weight gain than it is with appeasement."

Lauren Muhlheim in ‘When your teen has an eating disorder‘

"There is another powerful belief that makes some parents wary of ‘too much weight gain’ — the belief that their child will become distressed, more depressed and ‘worse psychologically’ if they ‘gain too much’. There are some providers out there who share this belief as well, setting weight gain goals ‘their clients can accept’. The fallacy to this argument is that we are not talking about the average child or teen, we are talking about the one with anorexia nervosa. There is quite literally no weight, however low, that will placate an eating disorder."

Julie O’Toole, Chief Medical Officer of Kartini Clinic, in ‘Setting goal weights‘

Further down, in ‘The abandoned underweight’, I’ll talk of the outdated practice of deliberately setting low weight targets.

"I’ve found that the single most important variable—the safeguard that separates the valley of recovery from the valley of illness—is maintaining the weight range that’s right for me[…] A few pounds [down], it suddenly felt more comfortable to be hungry than full. A meal that seemed normal two weeks ago looked huge and daunting."

Emily Boring, in an enlightening piece ‘When in doubt, aim higher: What I wish I’d known about target weights in recovery’ Listen also on this podcast

The genetics of healthy weight

"The major determinant of body weight is genetic"

AED Guidebook for Nutrition Treatment of Eating Disorders (2020)

We are now seeing anorexia through a new lens, thanks to ground-breaking research into the genome, first reported on in 2019 . The Anorexia Nervosa Genetics Initiative (ANGI) found that the illness has a metabolic component. The study leader Dr Cynthia Bulik reported on this:

"One very important message is how critical it is to adequately renourish people with anorexia nervosa — especially in the United States, we often see that insurance companies will de-authorize treatment prematurely. So people will be discharged from the hospital before their bodies have had an opportunity to sort of re-equilibrate or stabilize at a healthy weight. And so this suggests that getting the metabolism stabilized again might be a very important — in fact core component — to recovery from anorexia nervosa."

Weight isn’t a designer item

When females in China were tortured to make their feet small, I imagine the shoe shops only stocked torturously tiny shoes…

I have used shoe size as an analogy for healthy weight, and of course, weight is a little more adaptable than shoe size. Most of us are comfortable within a range of a few kilos. Within this zone, we eat freely and our body has stability and health.

But we’re not that adaptable. Diet companies have told us for years that we can manipulate our weight to enjoy a fashion-driven body shape. We know people can get there, but in spite of willpower, rarely does their body let them stay there.

How clinicians work out target weight and why there are huge differences

It’s natural that you should want to know what weight you’re working towards. Yet there is no way of predicting this with any precision. The only certainty for almost everyone is, regain lost weight as an absolute minimum, then keep assessing how much more is needed.

Use any weight goal a bit like a weather forecast. An expert has done their best with the many variables, but ultimately, you’ll only know it’s sunny tomorrow… when tomorrow comes.

If tomorrow turns out to be wet, then you’ll cancel the beach trip. It is poor treatment indeed when a clinician decides your child ought to be well now, just because they’ve reached a goal weight.

What’s recommended

To predict healthy weight, or to estimate that weight may now be healthy, many factors must be considered. Here are a few from the APA Guidelines (2023):

- height and weight before the illness

- growth history plotted on a growth chart

- menstrual history

- current pubertal stage (which will help factor in growth spurts)

- bone age (e.g. through X-rays)

- assessment of skeletal frame

- the height of the parents

- Also crucial to any assessment of healthy weight are your child’s mental state and their behaviours.

In the real world, I don’t think many clinicians are equipped to use all of the above factors. And it might be a waste of resources anyway, as the result will still be… just an estimate. Only the experience of being well, mentally and physically, can provide the confidence that weight is now healthy.

Yet pronouncing on a goal weight is common. If most clinicians can’t or won’t use all of the above recommended factors, then how do they set goal weight? I’ll give you an overview of the two main methods they use. (More detail in this other post.)

The median BMI / percent weight-for-height method

Using median BMI is a bit like giving all girls of the same age the same shoe size. Or predicting the weather near you today based on the average rainfall worldwide.

The median BMI method doesn’t feature in any of the reputable guidelines, yet it’s still commonly in use. I think some clinicians don’t realise that it’s just a ‘middle-size fits all’ calculation, and that humans can’t all be well in the middle. You’ll know this method is in use if you’re told your child should be at ‘100 percent weight-for-height’ (or some other percentage). What that corresponds to is the median (or middle) BMI of a whole population of girls or boys of your child’s age. Being the middle, it’s going to under-predict healthy weight for half the patients, sometimes by a huge amount. Apart from your child’s sex and age, there is nothing individual about it. I take you through this sorry method in this post and in this YouTube.

Using a growth chart

The other tool that is commonly used is far better (but is still very approximate when used in isolation): plotting growth history on a growth chart. It uses your son or daughter’s childhood growth history to predict current and future needs. Past weight and height data are plotted on a percentile growth chart, and the assumption is that your child should track along the same percentile. I explain here how this can be wrong. For instance, as I say here, you can expect your child to have a growth spurt some time between their tweens and teens, and it could be big.

Using a growth chart in isolation is a bit like predicting your town’s weather today based on previous years — without looking a current weather fronts.

Huge differences in predicted healthy weight

Overall, the weights or BMIs presumed to be ‘healthy’ and conducive to eating disorder recovery vary mightily from one treatment provider to another (as shown in this study by Roots et al, described in plain English by Tetyana in ‘Setting a target weight: an arbitrary exercise?)

So what to do, if there’s no way of predicting healthy weight? Well, we could let go of weight targets.

Why are we even talking about weight targets?

Some clinicians I respect say there’s no need for a target weight. When they first see a child, it’s usually obvious that weight gain is needed. Later, weight will only be one of many indicators of health. And of course a healthy weight is not a single figure but a range.

"Restoring physical health (which includes being at a weight that is healthy for that particular person) is a necessary condition of recovering from anorexia. However, that does not mean that we need to identify a particular weight to aim for as a target for recovery."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley’s Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication

"We focus on using the body’s response to nutrition rather than a weight goal"

Lock and Le Grange, in FBT treatment manual

"While weight is one measure to use for judging clinical progress it is helpful to think of weight as reflective of a state of health rather than an end goal in and of itself. The healthy weight becomes that weight where a person is physically and mentally healthy."

Therese Waterhous and Melanie Jacob, Practice Paper of the American Dietetic Association (now the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics)

Here’s a reason for not talking about target weight:

"Reliance on targets is often a mark of the illness’ need for ‘certainty’. Later on in treatment everyone understands that it is other areas of life that will determine when someone has reached a weight that is good for them."

Esther Blessitt, Principal Family Therapist at Maudsley’s Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication

In other words, we don’t engage in the eating-disorder’s demands. Our poor children have an anxious focus on weight and they kid themselves that numbers will reassure them. Instead, we talk about health and wellbeing, and we help them to tolerate uncertainty. As they get well, they appreciate feeling good, they see that they haven’t turned into a blob, and they loosen their attachment to a number.

It makes a lot of sense not to discuss target weight while someone is very underweight:

"It’s not a topic that should even be discussed until well into the refeeding process. With a starved, paranoid cave person brain and a critical fear of even one pound of weight gain, no one should be tormented early in recovery by the idea of some number range they are supposed to reach, weeks or months hence."

Jennifer Gaudiani in her highly recommended book, ‘Sick enough‘

An argument in favour of a weight target

Now I’ll give you a different view, from therapists I also respect, which is that weight goals have their usefulness. These therapists find it useful to discuss target weight in therapy.

First, it is part of exposure treatment for your child’s fears around weight:

"By NOT saying the weight range target to the kid we would reinforce the idea that it is too scary or bad for them to handle."

Rebecka Peebles, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, personal communication

And then it helps focus the parents too, and we owe it to them as they are doing all the hard work of refeeding:

"We also have so many parents who really think their kid maybe has only 10-20 lbs to gain but actually they have 30-50, and it dramatically alters their concept of the work ahead to get an accurate number."

Rebecka Peebles, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, personal communication

And it may help parents and clinicians be on the same page:

"Some parents set lower thresholds for weight targets than clinicians believe are healthy. They may do this because they believe their child is constitutionally thin, to make it easier to re-feed, or because of their own weight concerns."

James Lock, co-author of the FBT treatment manual, personal communication

James Lock added that "Of course this is not most parents, but it is an ongoing clinical issue I hear about frequently." On parents’ forums I mostly read from parents who are very upset that their child is now ‘stuck’ at a low number, often announced by one clinician without consulting parents or the rest of the team.

How clinicians try to give an individualised healthy-weight prediction

A clinician may give you a very rough minimum ballpark, taking these into account:

- the extent of weight loss, or failure to gain weight or height prior to diagnosis

- plots on the percentile growth chart (but remember this is still a poor tool)

- photographs

- genetics (based on the build of family members)

- skeletal frame

- muscle bulk (muscle weighs a lot, and health requires body fat too)

Most usefully, a good clinician will guide you, based on:

- mental state (so keep updating professionals on your child’s behaviours or beliefs)

- and physical state (using more or less sophisticated measures, like return of menses)

"A person’s healthy weight is highly individual to their genetics, their medical history, their experiences with food and dieting/caloric restriction throughout their life, and their body’s unique responses to inadequate fueling and to nutritional rehabilitation."

Dr Jennifer Gaudiani, internist and expert on the medical complications of eating disorders, in ‘Weight goals in anorexia nervosa treatment‘

"A “biologically appropriate weight” is a weight that is easily maintained without need for dieting or inappropriate food and exercise behaviors, and reflects pre-morbid weight, normal physical and psychological function, genetic predisposition ethnicity, gender, and family history"

AED Guidebook for Nutrition Treatment of Eating Disorders (2020)

"Weight has to be determined on an individual basis"

Daniel Le Grange, co-author of the FBT manual, in this webinar

Aim for higher

There are many first-hand accounts of people needing to exceed the predicted weight. That could be because the prediction used a terrible method — remember that ‘100 percent weight-for-height’ fails half of our kids. It could be that a growth spurt was due. It could also be that the prediction would have been pretty good in ordinary times, but this person needs ‘extra’ to really recover. More on this further down this page.

Cynthia Bulik, who researches the genetics of eating disorders, explains in a conference talk:

"Does adequate renourishment need to be done in order to reset metabolism? One of the things we have anecdotal evidence in is that re-admission to many programs is lower if you can get a person’s weight up even higher than their projected weight based on their growth charts […] We definitely need adequate renourishment to reset that perhaps […] poorly-wired metabolism."

A weight target will need to be adjusted… or let go of

Even with what looks like a well-individualised weight target, nobody should get attached to a number. As your child’s weight goes up, there will be more clarity on what he or she needs for a healthy physical and mental state.

"In adolescents, target weight will be adjusted upward to correspond to increases in the patient’s height, and it can be helpful to discuss this with them from the initiation of treatment. During a period of growth, the target weight should be reassessed every 3–6 months.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline 2023 page 33

"A range of 1-2 kgs on either side of the "target" allows for professional and parental judgment to contribute on whether weight gain is sufficient for health and growth, and based on the changes in THINKING and BEHAVIOR, which are really what need to change to recover from AN even if weight-restored by any definition."

James Lock, co-author of the FBT treatment manual, personal communication

Note that if you mention "1-2 kgs on either side" to your child, it may be very hard to keep raising weight if, as often happens, it turns out they need a lot more. I recommend you set higher expectations, or take the focus off numbers:

"The focus should be not on weight per se but health. This would include absence of signs of malnutrition (such as amenorrhoea, pubertal delay, feeling cold, bradycardia etc.) as well as presence of indicators of healthy functioning (e.g. expected growth velocity for age/stage of puberty, resumption of periods etc.). There will be also psychological indicators such improvements in mood, reduction in ED cognitions etc., etc. In this broader context weight is also relevant as long as we recognize the limitations of the information it provides."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley’s Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication

Here’s from one of several blogs on the subject by Julie O’Toole:

"At Kartini clinic, we try to focus on ‘state’, not ‘weight’. That is, the state of good health as opposed to a given weight. As measures of this state of health, we use our metabolic labs, including measurements of thyroid health, sex hormones, leptin, glucose, insulin, cortisol and others. We also look at the return of menstrual cycles (related to those same labs), return of energy and normal socialization.

Julie O’Toole, Chief Medical Officer of Kartini Clinic

What we don’t look at is BMI."

Clinicians use more or less sophisticated tests for physical health. Note that the return of several regular periods is a common indicator (necessary, but not sufficient) for girls.

But your child should not be deemed to be weight-restored just because their physical signs are normal again. You absolutely must update the professionals about your child’s behaviours and mental symptoms.

Tell the clinicians if you see signs of extreme hunger in your son or daughter. The eating disorder will complicate all this, but is your child hinting they want more? Are their eyes lingering on the bakery’s window display? Does your child have binges (real or imagined)? Many consider this as an indication that the body needs more nutrition, more weight, and that the eating disorder won’t go until it gets it.

Fitness-lovers who are all muscle and no body fat

In the fitness world, the aim may be to ‘improve’ body composition, meaning an increase in muscle and a decrease in body fat. A normal or high weight may hide a huge health issue due to insufficient body fat. This is because fat is necessary to many biological processes. Body fat does so much for us, we should think of it as an organ.

A deficiency in fat has long been recognised as ‘Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S), previously named the ‘female athlete triad’. In female athletes, one sign is absence of menstruation. Body-builders know how terrible they feel mentally and physically as they work on cutting body fat ahead of a competition. With males, an over-emphasis on lean muscularity should raise alarm bells just as much as weight loss or emaciation.

Clearly, the emphasis must go to gaining body fat and halting the muscle-building efforts. This is difficult when exercise is compulsive — a common issue with eating disorders.

* Exercise compulsion with an eating disorder – what can we learn from others? *

* One minute YouTube from Dr Jennifer Gaudiani: Body fat *

* ‘Should you be concerned about your son?’ by Scott Griffiths *

Youngsters who were ‘always’ at the low weight end

Has your child been very light, very slight, since they were a toddler? Perhaps they’ve needed to be on a higher percentile for a long time. We know for instance that when kids drop off their weight trajectory at an early age, they are more likely to be diagnosed with anorexia in their teens (see the paper here and a layman’s summary here).

Why did they drop? Maybe it was ‘normal’ for them, but could they possibly have started under-eating because of anxiety — for instance as they started nursery school? Or because there were too many foods that they felt wrong, as can happen with ARFID?

"Anxious kids may manage primary school tummy aches with restricted eating during the school day. Even 3-year-olds learn that thinner is better. I have had multiple teen girls disclose restriction on and off since kindergarten before they fell off the cliff.

JD Ouelette, personal communication

Here’s an example from Dr Peebles, talking about a child born at a normal weight who dropped off and then stayed on the 3rd percentile BMI for their age:

"and if there appears to be no reason for them to always have been so small, we’re often pushing for the 15th to 25th percentile BMI-for-age so that we can give them a robust chance at not having difficulty with eating.

Rebecka Peebles, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 46mn into podcast ‘State not Weight’

This is yet another example of how we must be cautious with percentile growth charts — we should not assume that a child must track along a centile curve.

Larger-bodied people (and fat stigma)

Weight loss in youngsters is automatically a red flag. Combined with eating disorder symptoms, it’s a no-brainer that weight must go back up. This applies to any kid, and any eating disorder — not just anorexia.

While emaciated kids get medical attention, there can be a lack of attention to simple weight suppression. Kids who lost weight but still have a ‘normal’ BMI (because they started off at a high weight) — these kids are in danger. (As explained in my post on weight suppression and in my post on ‘atypical’ anorexia). In the wrong hands, they get praised for now being at a ‘healthy’ weight, and are encouraged to stay that way. It’s awful, and it’s one of so many reasons why eating disorders need specialist treatment.

"In individuals who lived in higher weight bodies before the onset of their ED, such as those with atypical anorexia, refeeding and weight restoration should proceed with premorbid usual weight taken into account in determining weight restoration goals."

AED Guidebook for Nutrition Treatment of Eating Disorders (2020)

I feel the AED guide (quoted above) is being cautiously vague with the phrase "taken into account". Some therapists and parents are ambivalent about bringing youngsters back up to the higher end of the weight range.

We should reflect on whether a high weight suited our child: were they healthy, did they feel well within themselves, were their eating behaviours well balanced, and so on. When we reflect on their psychological wellbeing, can we disentangle the effects of any body-shaming from peers, in our harsh, fat-phobic society? How can we apply the limited evidence available to get to the weight necessary to beat the greatest health risk to health of all: the eating disorder?

Here are the views of some experts:

Julie O’Toole, who covers the topic in ‘Determining ideal body weight‘ and in ‘Coming to terms with my daughter’s genetically programmed body size‘. Rebecka Peebles explained to me how she talks to youngsters and their parents about a weight target around the start of treatment:

"Prior larger bodies kids get a minimum of 75th percentile BMI for age and a max of wherever they lived before"

Rebecka Peebles, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, personal communication

More on this from Dr Peebles, 47 mn into her podcast with Laura Collins Lyster-Mensh: Episode 21 ‘State Not Weight‘. She also gives a super-informative webinar on YouTube.

"We often encounter patients and families who say “but they looked better when they were a few pounds less” and want to use the eating disorder as an opportunity to keep a person’s weight suppressed. We believe that using an eating disorder as an opportunity to avoid returning to a previous higher weight could hinder the individual from reaching full recovery"

Lauren Muhlheim, ‘How we set recovery weights’

It’s important that all parties can have respectful conversations to work out the best path for an individual. I have heard of parents being accused of being fatphobic for asking questions. The truth is we all want to work out what’s best for this person. The most detrimental factor in their life is the eating disorder. And it’s also valid for parents to seek to understand the whole risk assessment picture. To help you with these questions I recommend you head over to this excellent video from therapists Kiera Buchanan and Audrey Raffelt, ‘Atypical anorexia or weight stigmatised anorexia?’, relating to their ICED 2022 presentation. The whole lecture is brilliant, but for questions like, ‘Won’t it be unhealthy to bring weight all the way back up, and in any case my child won’t cope’, jump to 30 mn in.

I say a lot more on these pages:

* Atypical anorexia diagnosis? Handle with care! *

* How to overcome weight bias and fat phobia *

Should your child be told about a target weight?

Some clinicians explain to the child the weight they’re aiming at, and some don’t.

"Typically, the target weight will be discussed explicitly with the patient, but this can require considerable sensitivity. On occasion it may be judicious to delay this discussion until the patient is less fearful of their ultimate weight."

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline 2023 page 33

What’s for sure is that the child needs to know that the whole team is focused on the need for weight gain. That can’t be a secret:

"As long as this message comes across as caring and an expression of a wish to promote long term well being (rather than being controlling and unwilling to listen) most young people with anorexia go along with the need to gain weight, albeit grudgingly and with perhaps (unpredictable) meltdowns. We have argued that, as long as the message about the need for weight gain is experienced as an expression of care, the young person, in spite of being scared, finds it at some level reassuring."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley’s Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication

Be really careful with any numbers you say aloud. Our children can fixate on any given target as their maximum. Giving a range can be just as problematic:

"As a HAES provider, I have moved toward setting a minimum weight rather than a weight range for my patients […] A weight range implies that there’s a weight above which they’ve gone ‘too high.’"

Dr Jennifer Gaudiani, internist and expert on the medical complications of eating disorders, in ‘Weight goals in anorexia nervosa treatment‘ (HAES is ‘Health At Every Size’)

As we saw, some therapists consider that talking about weight is part of the therapy. Parents, you can ask for an appointment without your child, in order to learn more:

"We walk the parents through a step by step explanation, with their kids’ historical curves. We then let them know it is our recommendation to only tell their kid the highest number in the range, as the kid cannot ‘unhear‘ the lowest number."

Rebecka Peebles, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, personal communication

Parents and youngsters need different conversations:

"We then tell the kid the highest number – with phrasing like, ‘A goal weight is just our best estimate of where your body and brain will work best. It’s also going to move up as you get older and/or taller, so the goal is a moving target and will go up. It’s based on where you were healthy long before this illness. Because kids grow all the time, any number we say is going to probably be the highest you’ve heard and it will probably feel upsetting, but it’s important we go over it so that you’ve heard it and the numbers seem less scary over time. Keep in mind that we are flexible on your goal weight and if your brain and your body are completely better earlier than we think, that’s fine. Likewise if you’re not totally better or not thinking clearly at the number we say now you may need more. We are fine as long as you are really truly fine and your eating disorder is gone.’

Then we tell the kid the highest number in the range. Watch the meltdown. And then keep going."

Rebecka Peebles, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, personal communication

Often, the meltdowns happen not in the therapist’s office, but in the car on the way home. The parents need all their parently skills to weather the storm (see chapter 14 of my book) and make sure the next meal is eaten (in particular chapters 6, 7 and 8 — there’s also loads in my Bitesize audio collection). parents can do this a lot more confidently when there’s teamwork with clinicians.

Note that Rebecka Peebles, whom I quoted above, is not dogmatic about telling all kids their target weight: "If I see a 7 year old who has no concept of weight at all, then we won’t. If parents refuse permission we won’t. But it’s really hard to do good work without being transparent."

When a child is declared ‘weight-recovered’, with no consultation with parents, without any careful assessment of their physical and mental state, usually using a middle-size-fits-all figure, we parents have to jump into damage limitation mode.

"When my daughter, still quite ill, came home from an individual therapy session saying, ‘She told me I’m at 100 percent and that’s my perfect weight’, I replied, ‘I’m sorry you heard that. Nothing is changing before all the adults review this together."

Eventually, if a therapist will not engage in discussion and insists that the weight given by their calculator is what your child needs, you might have to tell your child, as I once did to mine, ‘I’m sorry darling, I’ve studied this and I know better’.

Should your child see their weight? Blind versus open weighing

The question of blind weighing versus open weighing is hotly debated. I’ll keep it brief here.

Blind weighing is where your child is weighed with their back to the scales. Its purpose is mainly for the adults to check on progress. Usually, as the young person gets better, they stop caring so much about their weight, and when eventually they see the number on the scales, they shrug and get on with their lives. Sure, there’s a risk that they’ll have a meltdown and try restricting again because that part of the eating disorder was never addressed. But by then their brain function is probably greatly improved, and they may better be able to take in some psychoeducation about weight.

On the other side of the debate, is open weighing. The studies by Lock, Le Grange and others, which test out the effectiveness of Family-Based Treatment (FBT), used open weighing. Likewise for Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). The studies didn’t compare open and blind, but if you think of open weighing as a form of exposure therapy, it makes sense that therapists working to the FBT or CBT manuals view it as an essential component. These therapists use each weight reading as a therapeutic intervention, discussing fears, challenging beliefs, giving psychoeducation. Daniel Le Grange also explains in this webinar how knowing the direction of the weight is essential in FBT and how weight "sets the tone of the meeting".

If there’s chaos and trauma when your child knows their weight, watch below (at 44:20) how "rules are made so that you know when to set them aside". He also explains therapeutic value of open weighing:

From my discussions with parents, I note that many therapists who do open weighing do not do any therapeutic work around it. They weigh and let the parents deal with the meltdown in the car on the way home. The parents are unable to feed properly for several days (or worse), and weight gain is slowed down or reversed.

My opinion is that, on the basis of ‘First do no harm’, you can’t go wrong doing blind weighing at first, especially in the first visit to a generalist. This gives you time to find a good therapist who is skilled at open weighing, and ready to discuss with you the pros and cons based on your child’s mental state at this particular time. The principle, as always, is that you are an expert in your child, whereas the therapist is an expert in the treatment method.

For more on ‘The Pros and Cons of Blind Weighing’, I recommend this podcast with Karin Kaplan Grumet.

Is your child ‘stuck’ even though ‘weight-recovered’?

It’s highly likely that at some point in time, you’ll wonder if your child needs more weight, or more time, or more work on their behaviours and on normal life, or some kind of psychological intervention.

When the body is fine and the mind isn’t even close, it may be a sign that:

- more weight is required because the method used to set the weight target was very inaccurate — see my other post in which I warn of how very wrong some targets can be

- or that more weight is needed because the body needs to heal or to drive a growth spurt

- or that other aspects of treatment still need to be addressed (because weight-restoration is necessary but rarely sufficient)

- or that more time is needed for brain healing to catch up with body healing

- or that time is needed for life to bring maturity and richer interests

Sadly, children are often discharged from treatment as soon purely on the basis that they’ve reached a target weight. When parents point out the behaviours and thoughts that still afflict their child, some get told, ‘There’s nothing more we can do’, or ‘ ‘It’s time that Annie takes responsibility for her recovery.’

The children still have a long list of fear foods and fear situations, and they’ve never had guidance to practice small, safe doses of autonomy. Some need more psychotherapy input too, and everyone needs to build a life worth living.

If you’re in this situation, know that there’s a lot more to treatment than weight gain, and if you can’t get a more experienced clinician, there’s guidance to do it yourself (more in Chapters 9 and 10 of my book, and my Bitesize audios).

Perhaps you’ve worked on fear foods, behaviours, a rich life, and your child still has eating disorder thoughts and/or rituals. These could be mild, or still considerable.

It’s particularly common for body image issues to require more time:

"There is general agreement among clinicians that distorted attitudes about weight and body shape are the least likely to improve with weight restoration and typically lag changes in weight and eating behavior"

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) Practice Guideline 2023

You are dealing with uncertainty, and that’s normal and it will help if you make peace with that. Does your child need more weight? More time? More freedoms to engage with a richer life? There is no science to tell you which. So you’ll need to try things out, then review. I wish you great clinicians to support you through this process.

One of the variables to experiment with is more weight. We have a big number of first-hand accounts of youngsters who were ‘stuck’, until they were supported to get more nourishment and increase their weight by a few more kilos, or another 10 percent. Or by more than that. We hear that wonderful phrase, ‘My kid is back’. (See for instance Katie Maki’s account of the years supporting her child on 6000 calories a day).

An expert will see how patients do at their best estimate of a healthy weight, and if symptoms continue to be strong, they will bring the weight up. They’ll then assess the person’s physical and mental state over a short period, and if necessary, keep going.

You might think of this as a series of steps and thresholds, experimenting to see what suits the person. Do you have medication that’s been dosed that way? (For me, thyroxine and estrogen).

Some parents and clinicians are really nervous about bringing weight up. They’re scared it will drive their child to rebel and restrict. But what’s new? They’ve already proved they can support their child even through these ‘I feel fat’ crises. Perhaps they share their child’s resistance to a less thin body, because our society privileges those who are thin. So ask yourself: if there was a chance of saving a life using a medicine that caused weight-gain, would you have any hesitation? We must all do a little self-awareness and detect if we are suffering from a whiff of fat-bias. In this society, it would be strange if we were immune.

"Even treatment providers may be susceptible to weight stigma encouraged by society’s war on obesity. Consequently they may err on the side of under-restoring a teen in recovery."

Lauren Muhlheim in ‘When your teen has an eating disorder‘

"Unfortunately, many medical professionals, nutritionists, life coaches, and therapists have not yet done vital work on understanding their internalized thin biases, and they end up subscribing to and recommending practices that are grounded in diet culture. This is very harmful for everyone, but particularly so for those recovering from eating disorders."

Dr Jennifer Gaudiani, internist and expert on the medical complications of eating disorders, in ‘Weight goals in anorexia nervosa treatment‘

More than the minimum necessary: build a buffer

Many individuals have seen very clearly that if weight drops a little, eating disorder symptoms return in all their former glory. This illustrates the notion of a minimum weight needed for wellbeing.

"As soon as she would hit 1 pound [0.5 kg] under [xxx weight] the ‘voices’ and behaviours would come back with a vengeance. So now during exams she ups her fat intake a lot. She doesn’t weight herself but she just knows because of the thoughts."

The mother of a 20-year old

To avoid living on a knife edge, wise clinicians will help you factor in a buffer.

"My relapse taught me that for my own body, the difference between health and illness can be quite a narrow margin, just a handful of pounds. The simplest solution? Don’t live so close to the boundary."

Emily Boring, in an enlightening piece ‘When in doubt, aim higher: What I wish I’d known about target weights in recovery’ Listen also on this podcast

Teens may fight the idea of even a small buffer because they’ve made their ‘weight-recovered’ number their psychological maximum. This stops their recovery because they get back into controlling their eating and exercise, for fear of going into the feared zone above their magic number. To me that sounds like a good reason to use principles of exposure therapy and let them experience that nothing bad happens one or two kilos above. I believe they need that flexibility because it’s normal for weight to vary by plus-or-minus 1.5 kg or so in any given month or day.

Overshoot: needing some ‘extra’ for growth or healing?

Among adults in recovery from anorexia or another eating disorder, there’s a theory that to recover, your weight needs to overshoot (see for instance Emily Troscianko, Tabitha Farrar, Amazonia-Love, Helly Barnes).

‘Overshoot’ usually means that for a while, the body needs to go higher than the pre-eating-disorder level. Then it may or may not drop back down to the pre-illness trajectory.

The idea is that the body needs ‘extra’ to complete various bits of mending and to know it’s safe to return to normal functioning — the famine really is over.

With tweens and teens, the body may also be busy driving a growth spurt.

Some adults report that their overshoot was a biological drive, as they experienced ‘extreme hunger’ after years of restriction and underweight. They describe ‘mental hunger’, where there’s a drive to think about food and to keep eating even though they’ve eaten lots and feel full. They recommend that people honor this hunger, rather than fear it.

When people talk of ‘overshoot’ I see two different things being described:

- Going above your pre-illness level and staying there.

- Or going above your pre-illness level, then after a while finding that your body naturally dips back down to pre-illness level… without any deliberate restriction: you’re just less hungry.

You’ll find numerous personal accounts of both types of overshoot, where people achieved total freedom from an eating disorder.

With teens, many parents say how ‘overshoot’ was instrumental in their child’s recovery. What happened after the overshoot? Some youngsters stayed happily on a higher weight percentile. Others gradually dipped back down to a pre-eating-disorder level (in terms of weight percentile, rather than in actual kilos). I suspect there are many varied experiences, and that in any case, when it comes to expected growth trajectories and weight percentiles, we are dealing with a lot of variability.

Is a dip a welcome sign that the body now has all it needs and is stabilising to pre-illness levels? That would be fanstastic.

But we do have to be on the alert. Is our child covertly restricting again? Or perhaps they are not eating enough because they don’t yet have reliable appetite, hunger and fullness cues (because of their time being underweight, because of anorexia, and maybe because they were not born with a well-regulated system)?

Here’s an example of overshoot, leading to lasting recovery — the overshoot was followed by gradual dips in weight which were not linked to restriction:

"While she was having growth spurts, her predicted recovery weight (RW) was not enough. We took her to RW plus 30lbs, and there her voices and behaviors stopped. It was absolutely the magic wand.

A mother

Around age 17 the growth spurts stopped, and even though she was eating the same, her weight slowly dropped by 10lbs. She stabilised there for two years. Then at age 20, she slowly lost another 10 lbs, still without restricting. So now, at almost 21, her weight for wellbeing is stabilised at RW plus 10 lbs.

When she was losing, at first I thought it was due to relapse, but I see her eat 5 of her 6 meals, she is eating the same way, snacks freely, no exercising, not vomiting. There are none of the telltale signs I’ve learned to identify: she’s not striving for perfect grades, she has friends over all the time, her room is messy, she can wear non-baggy clothes, there’s no drama or odd behaviors around meals, and the non-stop negative self-talk has gone.

I have to add that when she first naturally started losing the weight I freaked out and severely and secretly upper her calories, and watched her like a hawk. She still lost. Then my own mother reminded me that as a teen, I was large and I naturally lost in my early 20s."

While some, like this mother, are sure that overshoot was essential to them, is that the case for everyone? For those who needed it, was the ‘extra’ the factor that got them ‘unstuck’? Or did the magic happen because while gaining more weight, they were also getting essential ingredients of treatment: it takes time to work on reduce fears, to normalise behaviours through exposure and repetition, and to rebuild a life worth living. It’s normal for mental healing to lag behind physical healing. The answer is probably different for different people.

There are no clinical studies on overshoot, and it looks like many clinicians don’t believe there’s a need for it, though they may also be open to having research done:

"It has not been our experience that further weight gain helps, except in the case where the recovered weight has been set too low"

Julie O’Toole, Kartini clinic, in her blog

Adults describing their ‘overshoot’ process say that the dip and downwards stabilisation happened naturally. They were not making any deliberate attempt to reduce food intake or weight. Simply, their period of extreme hunger ended.

We try to infer lessons from the Minnesota starvation study where adult men (without an eating disorder) overshot their previous healthy weight when their imposed starvation was ended. Once they were allowed to eat, it looks like their copious eating and their overshoot was ‘natural’. Does that mean it’s the only way to regain health? I ask because I see adults describing overshoot and ‘extreme hunger’ as a miserable and confusing time. Is it possible that things are different for our children, given that we have been supporting regular weight gain for weeks or months?

I think we don’t know enough to make universal overshoot recommendations. Clearly, it’s been necessary for many. And at the same time, many youngsters have recovered without overshoot. Maybe we can’t define ‘overshoot’ when there is so much uncertainty in what weight any child needs at any time.

We need studies that better reflect our children’s situations. Alternatively, as I previously suggested, we can let go of all that, accept uncertainty, and keep bringing weight up in increments while attending to all the other work of recovery.

The abandoned underweight

When you think of the dismal recovery rate quoted for various eating disorders, bear in mind that traditionally, patients were often allowed to stay underweight. Their weight target was based on a low BMI figure, or a low weight-for-height percentage. This still goes on in places. Indeed, let’s remember that ‘100 percent weight-for-height’ is a middle-size-fits-all figure, and so it’s bound to underestimate the needs of half of our children.

Let’s also remember those with ‘atypical’ anorexia nervosa, who are not told to regain lost weight because their BMI is now ‘normal’. These are the abandoned underweight too.

With adults who voluntarily attend treatment, there can be a fear that the patient will walk away, or will step up their restricting, if required to gain more weight. The clinician may also believe that a low weight is good enough for recovery. As a result people can live with not-too-bad a physical state — but their weight is too low, and their anxious control over food too high, for the eating disorder to ever be beaten. With anorexia, these people get the tragic label of ‘functioning anorexic’. Those who do a bit better may be considered in ‘quasi-recovery’.

Our sons and daughters need empathy and food, not a lower weight target.

What to do with all the uncertainty? Experiment and review

I’ll end with a reminder that weight restoration on its own doesn’t fix an eating disorder. But weight restoration is essential. What weight that means for your child: that is full of uncertainty.

My view is that we accept that we cannot know a recovery weight until we’re roughly there, after which we proceed in increments. As with everything which presents us with uncertainty, we can experiment and review.

"An important part of the later stages of the process of recovery is to accept that one needs to learn to tolerate uncertainty. This is a difficult piece not just for the recovering young person but also for the parent — and in different ways for the clinician. It would be wonderful to be able to have something specific and measurable that would tell us when it is safe to back off and let the young person get on with their life – if only."

Ivan Eisler, Maudsley’s Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, personal communication

More help from me:

* Experts say, "Recovery weight must be individualized" *

Quotes from eating disorder experts on weight targets: researchers, professional bodies, and the clinicians who may well have trained your clinicians!

* Is your child’s target weight a gift to the eating disorder? *

Comparing two methods therapists use to determine a weight target: growth chart + adjustments, versus the one-size-fits-all BMI approach. The difference can be huge!

* What do BMI and Weight-For-Height mean? *

What BMI and Weight-for-height (WFH) and BMI z-scores mean, and how they cannot be used for advice. Read this if your child’s therapist uses BMI or WFH.

* Weight gain in growth spurts *

To help you let go of weight targets, I remind you that youngsters’ growth is unpredictable and can go in spurts.

* Weight centile growth charts: why they can’t predict your child’s recovery weight *

How growth charts cannot predict a healthy weight for your child: I show you how they fail to show normal variations in healthy individuals and remind you that you won’t know your child is weight-recovered until they get there.

If your child has failed to gain weight with age, or has lost weight, that’s weight suppression. Make sure your clinicians aren’t only looking at your child’s current weight: here’s evidence that the amount and speed of weight loss matter at least as much.

* Atypical anorexia diagnosis? Handle with care! *

What’s ‘atypical anorexia’, the issue with weight being declare ‘normal’ or high, the risk from malnourishment and the need to regain lost weight.

* More on weight and feeding in Chapter 6 of my book *

From others:

* More on target weight on the excellent, parent-led FEAST site: ‘Setting target weights in eating disorder treatment‘

* Poodle Science: a YouTube from Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH): A short fun video that makes the point that one size does not fit all

* The importance of sufficient weight gain is beautifully covered by Dr Peebles talking to Laura Collins Lyster-Mensh in podcast Episode 21 ‘State Not Weight’ *

* If you want more on the theroy of ‘overshoot’, check out Dulloo et al, who after analysing the Minnesota men’s weight data, hypothesized that the great hunger and overshoot are autoregulation mechanisms to recover both fat and lean tissues (Emily Troscianko translates this in layman’s terms).

Thank you to James Lock, Daniel Le Grange, Ivan Eisler, Esther Blessitt, Rebecka Peebles, and a whole lot of well-informed parents, for helping me write this post.

Last updated on:

Comments

Thank you very much , I will start to communicate with my parents more and fill them in as much as I can. I also talked with my parents about the feeling and we’re working through it

Have a beautiful Christmas !

-The 13 year oldAh, you've done exactly the right thing! I'm delighted!

Eva

Hey,This is the 13 year old again What should I do? Today I faced a trigger by one of my parents which makes me want to restrict so much tomorrow and I know in my case when I restrict It becomes very severe very fast What should I say to these thoughts and voices?

Dear Anonymous, I am so sorry you are experiencing these difficult triggers. One day, you will stable and nothing will trigger you! For now, please know I help parents to help their child, I don't help the young people themselves. So I would encourage you to keep up the communication with your parents so they can best help you through these difficult times, rather than be asking ME. And of course I can help your parents if they want to come for example to one of my workshops, or to read my materials. Love, Eva

What about hair falling out ? I have a 13 year old at home who is dealing with strands of hair falling out at a time. Is this a sign she should gain more weight even if she is apparently weight restored?

Your opinion would be greatly appreciated

Hi Meg, a doctor will have the expertise for all the reasons hair may be falling out. However, "when you hear hooves, think horse, not zebra". The most obvious one in this context is indeed, malnutrition, which could indeed mean nowhere close to weight-restored (if periods are not back that would be another sign) or maybe there are restrictions of particular food group so essential nutrients for hair are lacking. I hope this helps you with the courage to keep going.

Hi, concerned parent here what if my child is supposedly weight restored but yesterday morning nearly started to skip breakfast again does this mean she still needs to gain some more weight?

Hello Sam, almost everyone will relate to your question, because it's normal that worrying behaviours or signs pop up for a while, and then we wonder if our child is going to sink all the way back down, or if we're missing some crucial element. Here's what I think.

Yes, maybe it's a sign she needs more weight. Always bear that one in mind.

However weight recovery on its own rarely fixes the eating disorder, as I explain in the heading above "Weight restoration: essential but not sufficient for recovery"So if for now you're pretty sure your daughter is weight-restored (and that her current meals will keep her on that growth curve, i.e. the weight keeps going up, her nutrition needs are being met) then you could focus your attention on all the work of exposure (chapter 9of my book) and of Phase 2 (chapter 110 of my book). I do a 'Phase 2' workshop covering both those aspects.

That work is necessary, but not sufficient: if it's not done, chances are high that a person will keep suffering from an eating-disorder

And weight restoration is also necessary, but not sufficient: without complete weight restoration, chances are high that a person will continue being anxious and resistant to progress, with a mind that continues to be beset by distortions.

So we parents live with some level of uncertainty when we see symptoms: is it that my child needs more weight, or more exposure and 'Phase 2' work, or is it both.

Given the uncertainty, we try and make wise decisions, experiments, small steps, and review from that.

I hope this helps. Love, Eva

What if my daughter is weight restored will she still need to be in taking a high amount of nutrients per day or can she go back to a persons ideal amount of nutrients per day?Your content has helped my family very much over this tough period Many thanks

Hey

I'm a 13 year old who is 3 months into recovery. Yay! I'm really proud of myself but how many calories should I be eating? I read I should be eating xxx calories per day and so far I'm doing it! But is this the right amount for me I would ask my doctor but my mom and dad are trying to help me without professional help I'm just wondering what you think:)Hi darling, you're using great courage and determination to get well – exactly what's needed, and yes, you sure can be proud of yourself! I've deleted some of your comment so as to avoid anything that might 'trigger' others.

So, you're 13, your parents are supporting you, and you'd like to know if you're eating the right amount, and you're getting taller. So it sounds like your parents are guiding you super-well and you can trust them! I imagine it's a bit nerve-racking to know where to put your trust… You say your parents are not getting professional help, but if they're guiding you to eat as you describe, I'm guessing they're very well informed – fantastic!

The standard rule is that the amount of food you need is whatever is bringing you back to your weight and height growth curves, plus a bit more to make sure your body really has what it needs, as explained on this page. And your parents will be able to give you the feedback about what your body needs, because you want both body and mind to feel great! You're aiming for a rapid rate of progress, even if that is stressful, so keep calling upon your courage.

Also, if your body is sending hunger signals, and you eat more than the numbers you've given me, that's great AS LONG AS you still eat the next meal or snack. (Missing meals or restricting on any meal, even if you ate plenty before, would set your body and mind back). If you don't feel hunger, that's normal too for now, and so keep up the good work in eating to plan.

You ask if I can hep you some more: direct your parents over my way, as I help parents to help their child.

Keep going and here's to your beautiful free life ahead!This is the 13 year old again I really appreciate that you replied also I'm sorry that I wrote with some words that may be triggering to others I will take better care in the future:)

You are very sweet! No worries at all — I'm super cautious about these things, and what you wrote for mild compared to much that is written elsewhere 🙂

My daughter is 13 and has worked diligently on her recovery. Her mood, her academics, her medical stats, her peer relationships are all improved. However, she has lost weight over the past several weeks and her dietician is stating that my daughter regain the weight she lost. Her growth chart has always had her in the 75th percentile as her "normal". When she entered treatment she was at the 50th percentile. She returned to the 75th, but now is back at the 50th. My daughter insists she is emotionally and physically much much better. Her pediatrician also says she is healthy. My daughter says she is happy at the weight she is and that she is not necessarily opposed to regaining the weight if she understands why the weight specifically is important. I am thinking I am over identified with her since I see her point. Weight is "just a number" and "only one indicator of recovery". I'd welcome your thoughts and input.

Hi Kat, I know well this confusing situation where we're trying to work out if we're over-identified, when we see our child's point… Hurray, by the way, for all this lovely progress!

Here's my instinct: you have a dietician who really knows your situation, giving you clear instructions, having presumably guided you all so far very competently. Sounds like this is a trustworthy professional. The paediatrician might (if they're not expert on eating disorders) be using more 'minimum' criteria for basic physical functioning, maybe reading a weight off a chart? Worth checking…

Consider that at 13, a young person must grow, not lose weight. The fact she lost weight may be an indicator that while loads of indicators have improved, that particular indicator is still flagging up a difficulty, possibly a rather crucial one, to do with her mental state, her attitude to food or weight, some of her behaviours… It may be that regaining the lost weight is part of giving the body what it needs for complete recovery, or more simply, that it gives her mind the practice and permission to find stability without restriction. It's common that our children restrict, once declared weight-restored, for fear of going above the magic number.

I hope you can have a private conversation with the dietician so that YOU really understand, which means then you can support your daughter with confidence.

I have a 15 year old who believes that she has stopped growing as her friends are all much taller but she remains not much taller than when she left primary school. She refuses to take on board that she is still growing and is very against putting on any weight since loosing around 2 stone. This is when we first realised we had a problem. The GP took too long to refer to CAMHS and we have now been on a waiting list for 5 months with only infrequent telephone calls and no sign of an actual assessment. Finding your book and this website has been a godsend. I feel like I finally have some guidance.

Dearest Jane, I am so very glad you have found some of the guidance you need. I do wish you lots of encouraging progress in helping your girl with nutrition. As for CAMHS, I believe they are currently fire-fighting and trying to prioritise, given what may be a 3 or 4-fold increase in eating disorder referrals (since Covid began). For that reason I would encourage you to a) keep telling them what you're managing and not managing; symptoms; worsening behaviours (and use Accident & Emergency if ever in doubt)

and b) do as much as you can from all the help in my stuff and in the stuff I link to from others in the UK and worldwide.

All my fond wishes, Eva

I am concerned for my child now in outpatient treatment who has remained on Xyprexa for 130 days, has experienced extreme hunger for weeks, and has reached the 90th percentile on her growth chart (her normal range was close to the 50th percentile through childhood). Could this hunger be a side-effect of medication and possibly interfering with her body's cues? I am deeply concerned for how her body will return to its set-point without triggering relapse. How far is too far for overshoot?

Hi Danielle

Yes I can see how you would want some good guidance on this. I think these are important questions to discuss with her treatment team. Both, on the management of Zyprexa, and on your questions regarding appetite cues, and weight. Sounds like you've been learning about 'overshoot'. and be aware this means different things to different people (e.g. for some it's just a little buffer). I don't feel competent to influence you on this. I'd say that as with most things with eating disorders, you get info from many sources, and then you and the clinicians discuss with care your own child's situation, as it may be different from whatever else you read about.

I hope you get competent support very soon. Love, Eva

Dear Ash, good on you to start treatment soon. That's a valid discussion to have with the therapist. I am sure you will be told the aim is to free you of ANY eating disorder, so that you will be healthy physically and will be free of both restricting and bingeing. I wish you lots of courage and swift successes.

i am not new to disordered eating. at my "start weight" i used to binge eat quite regularly. my weight made it difficult for me to engage in exercise, and made me a lot more uncomfortable during the heat and sun of summer. it was an unhealthy weight for me, and i am really scared that i will be forced to return all the way there. it is not even for aesthetic reasons: at a lighter weight i can enjoy exercise and feel a lot more comfortable in daily life. will i still be forced to go back to this weight, even if it was clearly unhealthy and unpleasant, and was the result of another type of disordered eating? i understand the importance of "eating without restriction" but essentially i would have to go back to binge-eating practically every day or so to maintain the weight i was at before- this seems counterproductive, as binging has been an issue for me long before restriction began. i am really worried about this as i am starting treatment soon, if anyone can answer my question it would be greatly appreciated 🙂

I am feeling pretty desperate with a 15 year old daughter who just will not follow the weight gain meal plan, says she can’t and won’t eat, despite our compassionate approach. She has been told by Camhs for the last six months that she is within the normal weight for height range but she is clearly too thin, has no periods and is now losing weight fast -despite an initial weight gain and despite still eating snacks and meals (albeit not enough) at each required time. She’s now below 90%. I just don’t know how we break the cycle of refusal – FBT doesn’t seem to be working at all, and I don’t know what will make things change. I have orders your book but wonder if you can point me to any particular strategies.

Dear Caroline, I feel for you as I know this horror of not being able to get your child to eat enough.

Since you've ordered my book, I think you will find many strategies in there as it's a major focus of the book. Sounds like you want at least one quick tip, and for that I suggest my 'bungee jump' video on YouTube. There are also lots of quick tips (which are also in my book) in my Bitesize audios.

Check also if your CAMHS has people who can help with meals at home — to break a deadlock and/or as coaching for yourselves. It's a bit rare, but worth asking for and trying.

It is a no-brainer that if she didn't recover regular periods, she had not reached a healthy weight. I am sorry that your CAMHS went by some one-size-fits-all figure instead of her own health indicators, and indeed if they're now talking in terms of 90% weight-for-height, there is a worrying implication that 100% (middle-size-fits-all) is the goal.

So what to do? You can make yourself super-informed so you can steer your daughter at home, and you can also — and this is more uncertain — ask for a review meeting, bringing in, say the psychiatrist at the head of the unit. I wish you good progress at this difficult time.

Eva

How do I, as a parent begin taking control of meals when my daughter will not let me prepare any food for her and refuses to eat anything I make .

A crucial question, Claire, which I address as thoroughly and helpfully as I can on this website, in my book, in my Bitesize audios. The shortest answer is my motto "Compassionate Persitence" and the "Yes but how?" is all over my resources. I wish you swift successes.

What a great article. Thank you. My daughter (19) is out of residential and now in PHP. We are struggling with why she is required to eat more when she “looks” restored. I feel this is creating anxiety on her part that she is now required to eat dessert everyday. I’m worried this anxiety over weight gain will cause her to go backwards in her progress. I know this is her fight but I have never dealt with something that feels like the family is left out of the process as much as it has. We are trying to support her at home but don’t feel like we have the tools even after she has been in treatment for months. Very frustrating.

Hi Jaci, it's a shame it feels like the family is left out of the process. That must feel incredibly frustrating, especially if you are worried that the clinicians are making unwise decisions. Good practice requires teamwork with parents.

Can you ask these questions directly to the PHP staff so they can explain it all to you? From what you say, it's likely that you will then be reassured that it is indeed a wise move. In general, we should not fear our children's anxiety: the aim is to support them through whatever it is they need, including any necessary weight gain (what she 'looks' like may not be a valid measure), and she must also practice eating without restriction/fear foods (so the ability to eat dessert would come into it). With the repetition and the support, normally the anxiety goes. More in Chapter 10 of my book.

Parents' questions and concerns are always valid, so ask your questions, raise your concerns, and show you want teamwork.

I hope things are going to look up very soon, Love, Eva

What if a child is at 87% weight for height and looks healthy, has had periods return and is completely mentally recovered? What if she eats intuitively and a really reasonable normal amount of food? Is it okay to stop the weight gain?

Hi Eve, you're describing a child who has recovered all aspects of physical and mental health, hurray! Her BMI, for her age, is below the median, and indeed half the population, statistically is naturally below the median. She would also have to keep gaining weight to stay on her weight curve, as she gets older and taller. I don't know how many kids are genuinely recovered at 87%, as that is low, so if I was the parent I'd want to know the signs are real and it's not my child painting a rosy picture because weight gain is so very hard.

Sadly there are still many clinicians out there who hold inaccurate beliefs about healthy weight.

I recently had a discussion with a colleague who did not think a patient of ours could be unhealthy at their supposedly 'healthy weight', even though their blood tests and physical observations suggested otherwise.

I have at times even heard statements that such patients could afford to 'lose more weight' and would not need to weight restore at all. I do believe this comes from a place of ignorance, although I acknowledge how harmful it can be.

For any parent in such a situation share your concerns with your clinician. Very often you do need to educate and point out the most recent evidence (if in doubt refer to something like Jennifer Gaudiani's book 'Sick enough' which is very evidence-based).

If you are unhappy ask if there is another clinician who is more aligned with your views. People do hold different views in teams. Don't be afraid to challenge or ask for further clarification.

I know your comment will be incredibly helpful and validating to lots of readers out there. Thank you. And yes, there is so much help in Dr Jennifer Gaudiani's book 'Sick enough' and her podcasts and videos

LEAVE A COMMENT (parents, use a nickname)